Remembering St. Brigit’s feast day and the Greensboro student sit-in

Ken Sehested

Invocation. “Gabhaim Molta Bríghde” (“I Give Praise to Saint Brigid”). — Aoife Ní Fhearraigh (Scroll down to see the lyrics.)

§ § §

Tomorrow, the first of February, is the feast day of St. Brigit (aka Brigid) of Kildare (c. 451–525), Irish abbess known for her hospitality. It brought to mind one of my favorite prayers, which I designed as a piece of art (at bottom).

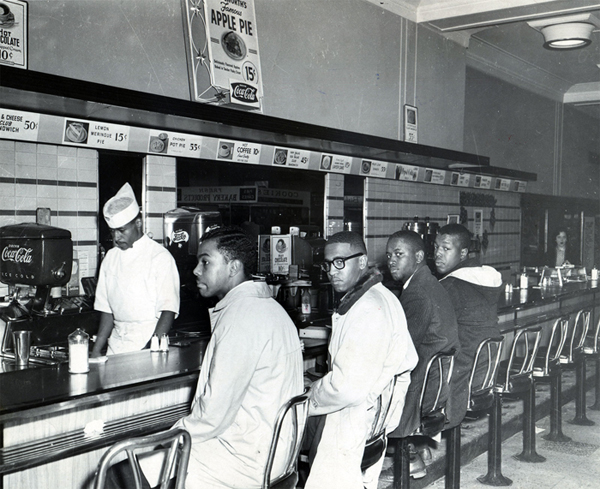

As it happens, tomorrow is also the sixty-sixth anniversary of the Greensboro, NC “sit-in” movement, when students at the North Carolina Agricultural and Technical State University demanded to be served at a segregated Woolworth lunch counter.

The extraordinary decision by those students to commit nonviolent resistance against injustice was not done on impulse. Much preparation went beforehand. This tactic had been tried before but did not spark of movement.

This one did, triggering similar protests in 55 cities and 13 states. One of my dear friends, then a student at Wake Forest University in nearby Winston-Salem, was among the first white students to join that action. (See George Williamson’s memoir, Born in Sin, Upended in Grace. For more on the inaugural sit-in, see “How the Greensboro Four Sit-In Sparked a Movement.”)

It’s instructive, too, to recall that most every major civil rights movement episode was initiated by local communities. Dr. King’s presence certainly brought national attention, strategy focus, additional activist s, and necessary funding. But the spark that prompted the blaze almost always came from localized leaders and networks.

s, and necessary funding. But the spark that prompted the blaze almost always came from localized leaders and networks.

The coincidence of St. Brigit’s feast day and the Greensboro action is a fitting framework to think of the kind of formation people of faith must undertake.

Clearly we need a beatific vision which Brigit’s prayer provides, I would say “mystical” vision, but the word in Englishmostly draws up images of esoteric hermits or rarefied saints. But, yes, a mystical vision, illimitable; a “thin space” experience where Heaven’s ecstasy and Earth’s agony overlay; a transcendent apprehension that, yes, “Earth has no sorrow that Heav’n cannot heal.”

Such intuitive grasp of the Beloved’s promise is essential if companions of Jesus are to withstand the inevitable storms and squalls of history’s rancor and hostility. Such an anchor is what allows us to face the rampaging powers, who mock the faithful, saying “you cannot withstand the storm,” and responding “I am the storm.”

A mountaintop experience, not unlike that of the story of Jesus’ “transfiguration,” when Jesus takes three of his disciples to a peak, where a glorious vision unfolds, where the Prophets Moses and Elijah appear. Impulsive Peter suggests tabernacles be built there. But no sooner had the rapturous moment ended, Jesus—ignoring Peter’s impetuous request—saying something to the effect of fugetaboutit and leads the three back down the mountain where they are immediately confronted by a man whose son had a “spirit” causing him to convulse, grind his teeth, and foam at the mouth, which some commentators think ![]() may have been epilepsy.

may have been epilepsy.

Jesus heals the boy. And thereby establishes the link between the ecstasy and epilepsy—between mountaintop spiritual experience and the healing of Earth’s destitute, diseased condition.

You may recall that this story in Mark’s Gospel (chapter 9) comes immediately after Jesus’ conversation with his disciples, asking, “who do the people say I am?” Peter gets it right—but not quite right. Then Jesus speaks to them of the trouble tocome, of his suffering and eventual crucifixion by Rome’s anti-terrorism task force. Whereupon Peter, in his insolence, adamantly rejects the notion that a sovereign should suffer, much less die!

We should also be thinking here about Martin Luther King Jr.’s “mountaintop” speech in Memphis—surely a beatific expression—where he had gone to support striking sanitation workers. Some consider that speech to be his most electric elocution.

“I’ve been to the mountaintop. And I don’t mind. Like anybody, I would like to live a long life. But I’m not concerned about that now. I just want to do God’s will. And He’s allowed me to go up to the mountain. And I’ve looked over. And I’ve seen the promised land. I may not get there with you. But I want you to know tonight, that we, as a people, will get to the promised land. And I’m happy, tonight. I’m not worried about anything. I’m not fearing any man.”

He continued, “Mine eyes have seen the glory of the coming of the Lord.” And the vision comes in the context of supporting the demand of sanitation workers for better pay and working conditions.

To sustain the struggle at hand we need St. Brigit’s visionary prayer of festive delight and exuberant gladness. But make no mistake, its lexicon—its field of vision—is infirmity, is animosity, is in every context of history’s affliction, even within our own hearts and minds.

St. Brigit’s vision, combined with the resolute bravery of the disinherited (supported by those who join them), chart the path for followers of The Way.

§ § §

Benediction. “I’m Gonna Sit at the Welcome Table.” —Birmingham Jubilee Singers

# # #