Ken Sehested

Invocation. “Lead me, O Lord, O great redeemer through the troubles of this world. Lord, I thank you for watching over me thus far. You are forever by my side.” —English translation of lyrics in “Ndikhokhele Bawo,” University of Pretoria Youth Choir

§ § §

Immediately following the dastardly terrorist attacks of 11 September 2001, I sat at a computer screen—in the secretary’s office of Austin Heights Baptist Church in Nacogdoches, Texas, far from home—for the better part of a day trying, desperately, to write something that made sense of this tragedy. It unfolded not only as a devastating body count but also a grievous psychic wound to the US national self-image.

(The article: “In the valley of the shadow: Reflections on the trauma of 11 September 2001.”)

This changes everything, I wrote.

I was soon chided for that remark by Ray, a Canadian friend—a theologically astute and socially aware friend—who responded that such tragedies are multiplied many times over in many parts of the world on a regular basis.

My purpose was not comparative, singular tragedies, I responded. In fact, the country of Chili has its own 9/11 woebegone memory: Of the 11 September 1973 coup d’etat overthrowing the democratically-elected government of Salvador Allende, bringing to power a right-wing military junta led by General Augusto Pinochet who ruled—with support from the US—for 27 years, killing or “disappearing” more than 3,000, torturing most of the other 38,000 political prisoners.

It’s the context of our terror memory that makes this such a grievous wound, in this one country (my own): Being the wealthiest in history, and being the most heavily armed, and having one of the most extensive colonial influence-peddling operations in the world (accomplished more by economic penetration and financial manipulation than by gunboat diplomacy), the US would likely undertake retaliation for a generation or more.

Sure enough, on the heels of 9/11, Congress passed a revised “authorization of use of military force,” which allows the president almost unlimited use of military force by simply saying “terrorism.” For the first time, legal justification for preemptive war. (And remember: the US has never made a no-first-use policy regarding nuclear strikes against our enemies. That preemptive option has never been ruled out.)

I remember a comment made by General John Abizaid, then head of US forces in Iraq, made a few months after the 2003 invasion of Iraq. He admitted that his troops face “a classical guerrilla-type campaign” and said that troops might have to double their expected tours of duty in order to pacify the country. After that, a special assistant to Donald Rumsfeld, secretary of defense under President George W. Bush, said about the unrest in Iraq: “This is the future for the world we’re in at the moment. We’ll get better as we do it more often.”[1]

A generation after the 9/11 attacks on the US, the recoil of that abominable day has spawned the ravenous and ruthless administration of our current president, his molesting cabinet, and his duplicitous judicial, legislative, and social media enablers.

Not to put a too theological spin on it, we are in deep doo-doo. As a nation-state, certainly. Small-d democrat institutions, rules, and norms are crumbling. Political commentator Ezra Klein recently said “This is not just how authoritarianism happens. This is authoritarianism happening.”[2]

As communities of faith, clearly, as the public posture of Christian congregations is not only dwindling but increasingly devoid of reference to Jesus (except as a mascot).

As former Time magazine essayist Lance Morrow wrote, “War is rich and vivid, with its traditions, its military academies, its ancient regiments and hero stories, its Iliads, its flash. Peace is not exciting. Its accoutrements are, almost by definition, unremarkable if they work well. It is a rare society that tells exemplary stories of peacemaking—except, say, for the Gospels of Christ, whose irenic grace may be admired from a distance, without much effect on daily behavior.” (Italics added.)[3]

As that anguished prophet, Jeremiah, moaned: “The harvest is past, the summer is ended, and we are not saved” (8:20).

The time of testing is upon us. The day of judgment will be disruptive. As William Shakespeare’s storm-tossed characters in “The Tempest” cried, “All is lost, all is lost, to prayer, to prayer.” Such is, I would argue, the truthful claim that the courage needed for the facing of these days comes from beyond human facility. Which is to say, transcendence is involved: a firmer footing, a deeper clarity, a capacity beyond what is thought possible.

Such transcending prayer, however, is not an escape hatch, not a head buried in the sand, not a “Hail Mary” (a desperation football play), not whistling through the graveyard.

Rather, prayer is the portal available to grace-shaped lives to envision another world, an earth cradled in Heaven’s Kinship, a re-created future when all shall linger ‘neath their own vine and fig tree, and none shall be afraid (Micah 4:4), the day when “all flesh shall see the salvation of God” (Luke 3:6).

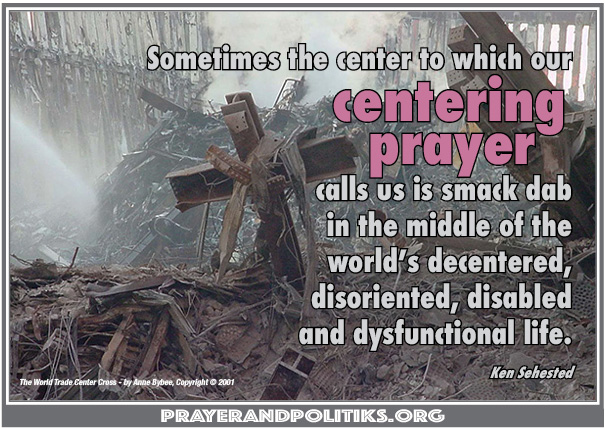

The call to prayer is not merely reclusive. Sometime the center to which our “centering prayer” calls us is smack dab in the middle of the world’s decentered, disoriented, disabled and dysfunctional life.

Such prayer conjures memory supplied in the Little Flock of Jesus’ two primary sacraments: baptism and eucharist. The first being a renunciation of the squandering world’s reliance on the myth of redemptive violence (as New Testament scholar Walter Wink so aptly called it); the second, the sheer joy of the bread-and-cup table of assurance that nothing can finally separate us from the love of Christ (Romans 8:35).

At this table we learn that we can risk much because we are safe. That not even mortal wound can sever ties with the Beloved.

The eucharistic meal is a repetitive reminder of our baptismal vows, vows which are safeguarded by the promise that, though weeping endures for the night, joy comes in the morning (Psalm 30:5).

It’s important to remember, though, that the eucharistic invitation is not for a happy-clappy life. As mentioned above, embedded in this invitation to blessed assurance and feast of plenty is the memory of the baptismal act of renunciation of “the world’s” modus operandi, of the incessant claim characteristic of profaned life that only the strong survive, that you get what you earn and you keep what you can protect.

As the fifth century BCE general and historian Thucydides commented, “The strong do what they can and the weak suffer what they must.”[4]

Integral to the infant baptismal vows in several denominations are these three questions: “Dost thou renounce Satan? and all his works? and all his pomps?” To which the parents reply, to each question, “I do renounce.”

To profess this renunciation is not simply to parrot the words but to foster a life devoted to the places where life has come undone, where the abused and forsaken congregate, to offer care not as a patron to a debtor but out of the conviction reflecting God’s preferential option for the impoverished and the excluded who have no place at the table of bounty.

We locate ourselves in compassionate proximity to the abandoned because it is in such locations that we are most likely to be attuned to the Spirit’s movement in history. Counter intuitively, it is in such circumstances that we find our own salvation, that our own breath is restored, and where the Kinship of God is announced.

Our very souls are at stake in the midst of this conquest by the haves of the have-nots.

As playwright Archibald MacLeish penned in his play “J.B.,” a modern retelling of the Book of Job: “Isn’t there anything you understand? It’s from the ash heap God is seen. Always! Always from the ashes.”

Between the baptismal soak and the table’s delightful feast, there is the Apostle’s call to mobilized training and outfitting, of “putting on the whole armor of God” (Ephesians 6:10-17). Such preparation is the sine qua non, the first and fundamental duty, of those on the Way of Jesus. The text is militant, a boot-camp stipulation, an exacting disciplining, like steel-on-steel sharpening. Living hopefully “in the world” is a risky business, for which rigorous preparation is essential.

Despite all apparent odds and most available evidence, hope is our rightful posture, rooted in a beatific vision, the provision of buoyancy in the midst of drowning billows. Ours is a faith that history is not fixed, that the future is not fated, that creation is not abandoned to its violent, predatious habits and corrupt predilections.

“To prayer, to prayer” . . . but, no, in the end, all is not lost. And thus we pray:

Blessed One,

Hallowed be Your Name; and thereby may your

consecration uphold us in the living on these

trying days. We confess that our faith, our hope,

and our love are oft under siege by the

powers of enmity, animosity, and

acrimony. Teach us to live within the bonds of

your strength rather than the pretense of our

vanity, so that we may stand against the wiles of

the Confuser. Remind us that only reverence can

counter the tides of

violence. In the struggle for earth’s proper

alignment with Your promise in Creation, and

your intention in Re-Creation, clothe us with the

attire that makes for life’s flourishing: with the

belt of truth to cinch every lie; with

the breastplate of righteousness that confronts

every injustice; with feet shod with the hope that

sustains against the bruising stones of despair;

with the helmet of assurance that averts the

arrows of insult and

contempt and shame; with the shield of faith that

denounces the spirit of confusion and the

temptation of despondence; and with the sword

of protection against the soil’s despoiling, the

water’s fouling, the

air’s poisoning. Most of all, help us to remember

that we are not loved because we are valued, but

that we are valued because we are loved[5]; and

that, in the end, love will outlast hate, kindness

will displace hostility, mercy

will trump vengeance—in our longing

for and leaning toward that day when all flesh

shall see the goodness of God in the land of the

living. We ask these things not for private gain

but for the common good, endowed in and

through the name of Jesus, our masterless friend,

and aspired by the Holy Spirit’s work twining the

heart’s desire with history’s consummation and

habitation of that Land which is fairer than day.

Maranatha. Come quickly. Amen.

§ § §

Benediction. “You do not carry this all alone. / No, you do not carry this all alone. / This is way too big for you to carry this on your own, so / You do not carry this all alone.” —“Carry This All,” Alexandra Blakely https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=uBhCFsatU0Y

# # #

[1] Quoted in Harper’s Weekly, 22 July 22 2003

[2] “Stop Acting Like This Is Normal,” New York Times, 7 September 2025

Weeks earlier, on her weekly broadcast, cable news reporter said the US is not headed toward an authoritarian state under President Trump, “We are there. It is here.” —“Rachel Maddow Warns the US Isn’t Headed for Dictatorship: ‘We Are There,” Tess Patton, The Wrap, 5 September 2025

“On Friday, September 5, Trump lawyer Cleta Mitchell told Southern Baptist pastor and Newsmax host Tony Perkins that Trump may try to declare that ‘there is a threat to the national sovereignty of the United States’ in order to claim ‘emergency powers to protect the federal elections going forward,’ overriding the Constitution’s clear designation that states alone have control over elections.” —Heather Cox Richardson, “Letters from an American,” Sept 8, 2015

[3] “To Conquer the Past,” 3 January, 1994

[4] Spoken by Athenians during the Melian Dialogue in Thucydides’s History of the Peloponnesian War

[5] Line borrowed from William Sloane Coffin