by Ken Sehested

Presented at the “Evangelism and the Peace Witness of the Church,” sponsored by the Baptist World Alliance & the Mennonite World Conference, January 10-12, 2002, Eastern College, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania

§ § §

“For the darkness shall turn to dawning, And the dawning to noonday bright,

And Christ’s great kingdom shall come on earth, The kingdom of love and light.”

—H. Ernest Nichol

I’m pretty sure it happened on a Saturday night. I was sitting on the platform in a small Baptist church in Louisiana, when it swept over me. My two colleagues, Willard and Freddy, and I—all of us still in high school—were leading a weekend “youth revival.” We were the snappy-dressed, somewhat flamboyant youth evangelist team up from the southern part of the state. We were known for lighting the fires of revival under local congregations, with special attention to the young people. If fact, one of my roles was to teach a course of personal soul-winning; and each evening following the service we took the church youth out to practice what they had learned, visiting the local Dairy Queens and Burger Kings, asking other young people if they knew Jesus.

I also played the role of counselor, the one who greets those who came forward during the hymn of invitation to give their hearts to Jesus or rededicate their lives or commit themselves to “full-time Christian service.” My persona as a star athlete helped sweeten the appeal, especially for the young women in the crowd.

In my religious subculture—revivalist, Baptist, Southern, Christian—it was not unheard of for adolescent young men to begin their preaching career. I had several peers who undertook the same journey.

The truth of the matter is that, as I now know, I experienced at age 14 a truly spiritual experience, with all the classic characteristics of such intensely personal encounters with God: a kind of dissolving of the ego; a sense of merging into God; a palpable sensation that I was nothing, and everything, at the same time; an inexplicable, joyful, but utterly serene experience of compassion.

Years later, the experience prepared me to receive the more expansive and expressive testimony of Thomas Merton when he described the extraordinary experience he had in Louisville, after which he wrote “at the corner or Fourth and Walnut, in the center of the shopping district, I was suddenly overwhelmed with the realization that I loved all those people, that they were mine and I theirs, that we could not be alien to one another even though we were total strangers. . . .” (Conjectures of a Guilty Bystander)

Unfortunately, my religious tradition has no categories for interpreting such experiences. When I reported the experience to my pastor, I was simply informed that I’d been call to preach. And since the work of traveling evangelists seemed more exciting than being a local pastor, that’s how I imagined my future. I was going to become the successor to Billy Graham.

But three years later came an equally unexpected experience, facing rows of mostly-filled pews in the New Light Baptist Church sanctuary, tucked in among the cotton fields south of Monroe, Louisiana. Only this time, instead of joy and serenity, I experienced a profound dissonance, confusion, near-disillusionment. I felt as if I was in a charade, mouthing words that were suddenly limp and vacuous, struggling to manufacture appropriate emotions. “What in the world am I DOING here?!” was the question that came to mind. I was secretly relieved that no one came forward that evening during the hymn of invitation.

I thought I was going crazy. Actually, if truth be known, I thought I was going to hell. Thankfully, not long after that unnerving episode, I went away to college, effectively ending my youth evangelism career. Although I didn’t realize it at the time, that briefly-paralyzing experience was the early-warning tremor of what would, in subsequent years, become a full-blown theological earthquake. After two years at a Baptist university I ran away to the sensuous and secular environs of New York City, determined to free myself of religious propaganda. As with my spiritual mentor of the time, Job, I had complaints to air with God and was determined to speak them vigorously.

Little did I know that my running was toward God, not away from God. The “dark night of the soul” is fearfully disorienting. As Providence would have it, I found tutors who did not fret over my theological kicking and screaming, who were patient enough to see through my hubris and self-pity, and who had the wisdom to introduce me, as if for the first time, to my radical Baptist and Anabaptist history, amid a wealth of other stories and narratives from Christian history. Over the course of about a decade I slowly overcame a profound sense of spiritual schizophrenia, of looking back at my photo on those old revival publicity posters and wondering who in the world was that person?

I’m beginning with this extended introduction in part to indicate how my topic—“A spiritual journey from individualist faith to concern for world peace”—is deeply rooted in my own personal narrative. And also for methodological reasons: Biblical spirituality demands that all theological reflection begin with narrative history. In other words, the real-life experience of the believing community, however faithful or unfaithful in its witness to God’s redemptive intention and movement, and however successful or unsuccessful in its confrontation with the powers of this “world,” is the only proper raw material for theological reflection. We’ve a story to tell to the nations—not a doctrine to be propounded, not an emotion to be mimicked, not a program of scruples to be enforced—that shall turn their hearts to the right. Personal testimony has been—and I hope continued to be—the primary form of theological discourse within the Baptist confessional tradition. A story of truth and mercy, a story of peace and light.

Healing and revealing

That we are having a conversation about the practice of evangelism and the pursuit of peace—and especially the relation between the two—is significant. Many years ago I thought the segregation of these activities was unique to my own Southern-flavored Baptist tradition. I now know that our inability to comprehend the intimate interrelation between these activities represents the major fault line running through, and frequently erupting within, every Christian body, both here in North America and around the world.

By and large we have failed to articulate the drama of biblical faith—its invitation for our participation to join what Clarence Jordan called “the God Movement”—in ways that coherently communicate the mandate to follow Jesus:

•to be captivated by God’s economy of grace and thereby align ourselves against all economies of repression and in favor of economies of manna (sufficiency);

•to be drawn into the disarming love of God and thereby implicate ourselves in the struggle against escalating armament and in favor of strategies for nonviolent struggle against injustice;

•to be so animated by the experience of God’s forgiveness that we are impelled to practice the politics of forgiveness as a realistic strategy for overcoming the politics of vengeance.

Let me refer you to three touchstone texts embedded in my thinking.

The first is a sentence from Genesis: “Now the earth was corrupt in God’s sight, and the earth was filled with violence” (6:11). In Scripture’s vision, the presence of (spiritual) corruption and (physical) violence are mirror images of each. The second is from Jesus’ model prayer: “And forgive us our sins/debts as we forgive those who sin against us/our debtors” (Matthew 6:12). In Aramaic the word for “sin” (a spiritual condition) and the word for “debt” (a physical condition) is the same. The third text is that initial missionary commissioning narrative in Luke (10:1-12). Here Jesus instructs his original corps of 70 evangelists to spread out across the land to gather the children of peace; and then, in a very suggestive line, he says: “heal the sick and say to them, ‘The kingdom of God has come near to you’” (vs. 9).

The mission of healing and revealing has always been a singular one for the believing community. We have preferred to split ourselves up as “evangelicals” and “liberals,” emphasizing “individualistic faith” or “concern for world peace.” About the best theology available to us seems to be advocating the “balancing” of these practices, consciously or unconsciously alienating “spiritual” matters from “earthly” or “material” ones. My claim is that:

•when such segregation occurs the Bible is effectively rendered innocuous and the community of faith made impotent;

•when “souls” are separated from bodies, from history, the consistent redemptive promise of Scripture—that the creation is to be redeemed, not renounced—is flatly and flagrantly denied by a confused church;

•only when we comprehend that, biblically speaking,“spiritual” realities are not categorically different from “physical” ones—it is much closer to the truth to say that spiritual realities describe certain kinds of physical, material ones.

When scripture is emptied of its inherent materialism, when it becomes domesticated, the result is legislation like that found in the Ecclesiastical Records of the State of New York: “It is hereby enacted that the baptizing of any Negro, Indian or Mulatto slave shall not be any cause or reason for setting them at liberty.”

The doctrine of the Incarnation is the most distinctive confession of our faith, and it is this: that God is more taken with the agony of the earth than with the ecstasy of heaven.

The heart of my argument is that: the very fact that we segregate material and spiritual realms of being is evidence that we are confused about the nature of biblical spirituality. (And this is true even when we talk about “balancing” concern for material and spiritual conditions.) To pursue this assertion I want to examine three premises:

•that while spirituality is always personal, it is never private;

•that the believing community is saved for the world, not from it;

•that in biblical narrative, conversion of the heart is inherently linked to transformed commitments counter to the reigning policies governing socio-economic and military security affairs.

To put this plainly, rarely any more do our hymns of invitation prompt the kinds of conversions like that of John Newton, the author of Amazing Grace, who abandoned his career as a slave ship caption in response to being overshadowed by God’s grace. Nor that of Zacchaeus, who framed his confession of faith in Jesus Christ as personal Lord and Savior in these terms: “Behold, Lord, the half of my goods I give to the poor; and if I have defrauded anyone, I will return it fourfold” (Luke 19:1-10). You will recall that Jesus did not lecture his new disciple on the dangers of the “social gospel;” rather, he simply said: “Today salvation has come to this house.”

A critique of Christian spirituality

The word spiritual has come to mean some pretty slippery and awfully greasy things in our time. Expatriate gurus with a taste for expensive cars use the word a lot. Have you ever been in a conversation where someone referred to another as a "very spiritual person" and wondered exactly what was meant? Generally it describes a person who exhibits regular habits of religious piety—folks who pray a lot, pepper their language with religious-sounding words. Evangelical Christians use the word a lot; but so do practitioners of transcendental meditation. TV preachers employ the word frequently, but so do a lot of vegetarians. A few years ago the newspaper carried an ad for BMW cars. The caption read: "For a spiritual uplift on easy monthly terms, consult your local BMW dealer."

Most notions of modern Christian spiritual reality are a lot like cotton candy: Coming at you, it looks bigger than life, but it's most air. And what substance there is will rot your teeth and turn your stomach. Our conception of spiritual reality is mirrored in the comment of the youngster in a Family Circus cartoon strip that appeared several years ago in a Mother's Day Sunday morning paper. The two children were talking, and the boy says to his sister: "I think I'm going to give Mom a spiritual bouquet and save my money to buy a catcher's mitt instead!" Worse—and more vicious—is the cartoon depicting a Salvation Army-type band playing and singing to a group of homeless men sitting on a river wharf. The band is singing the old gospel song, "Rescue the Perishing," completely oblivious to an unlucky one who has fallen off the wharf and is floating down the river.

Do you remember the advice Screwtape gave to Wormwood in C.S. Lewis' devotional classic, Screwtape Letters? In discussing the case of one particular human that Wormwood is attempting to subvert, Screwtape—the Satan-like central character of the book—offers this bit of advice to Wormwood, his disciple: "It is, no doubt, impossible to prevent his praying for his mother, but we have means of rendering the prayers innocuous. Make sure that they are always very 'spiritual,' that he is always concerned with the state of her soul and never with her rheumatism."

The difference between private and personal spirituality

The first confusion we face is that between “private” (or “individualistic”) and “personal” spirituality. In biblical terms, spirituality is always personal, but it is never merely private.

•As if salvation was like a supernatural inoculation, which stings a little but, after that, you’re good for eternity and free market rules apply.

•As if salvation was a commodity of consumption, purchased on some sort of divine lay-away plan (at discount prices in larger chain-store franchises), by acts of narrowly-defined religious piety and personal morality, with full “redemption” in the afterlife (although it pays to shop around for better interest rates).

•As if salvation was little more than a divine bookkeeping transaction, shifting the soul from the “debit” to the “credit” side of the ledger, a kind of “get out of jail free” card to spur us on our way to economic monopoly, an insurance policy to cover the ultimate contingency.

It is not by happenstance that the church’s preaching of privatized salvation is often confused with the consumptive appeals of modern marketing. Once, when my oldest daughter was still a young child, she looked at me in earnest innocence and asked if the man who had just finished speaking on T.V. was a preacher. “No,” I told her with a chuckle, “that man was selling used cars.” Is it a coincidence that ministers who forsake their pastoral careers often end up in sales? We live in a culture that spends $5 billion annually on special diets to offset the effects of gluttonous lives, while 400 million people in the world are so severely malnourished they are almost certain to suffer a combination of physical and mental incapacity, if not die of starvation. At best, most of our churches see the latter as a humanitarian tragedy; at worst, they are oblivious to this reality. In precious few cases do they see this travesty as a matter of spirituality.

The preaching of privatized, individualized faith reminds me of the line from that Greg Brown song sung by Dar Williams: “Lord, I’ve made you a place in my heart, and I hope you will leave it alone.” And you’ve probably seen some of those “alternative” gospel hymn titles, like: “I Surrender Some,” “Oh, How I Like Jesus,” “Take My Life and Let Me Be,” “Blessed Hunch,” and “Spirit of the Living God, Fall Somewhere Near Me.”

To quote Clarence Jordan again: “Faith is not belief in spite of the evidence; that not faith, that’s foolishness. Faith is life lived in scorn of the consequences.” Any revealing of the Word of God that does not entail the healing of creation is, to borrow from William Shakespeare, “full of sound and fury, signifying nothing. Or, more bluntly, from John’s first epistle: You are lying if you say you love God but hate your neighbor (i.e., if you live in oblivious disregard to your neighbor’s needs). (cf. 1 John 4:20)

Saved for the world, not from it

Certainly part of our confusion at this point has to do with the English translation of the Bible. For instance, we are instructed to "love not the things of this world. If any love the world, love for the Abba is not in them" (1 John 2:15). But, on the other hand, "God so loved the world that he gave his only son" (John 3:16). On the one hand, the world is said to be passing away (1 John 2:17); on the other, "God was in Christ, reconciling the world to himself" (2 Cor. 5:19).

Some time ago I was invited to speak to a Baptist conference on peacemaking. In her letter of invitation, the conference organizer asked me to speak on the subject: "Why should we get involved in peace when people just need to be saved?" I laughed out loud when reading it, momentarily wondering if this was her prank. Racing on through the letter, I thought surely she will get serious and list my real topic.

But that was the real topic. After the initial shock faded, I began to sense the title's appropriateness. Carol, I said to myself, you're a genius!

It had seemed clear for a long time that a key reason many church folk have difficulty in taking justice and peace issues seriously is because such concerns failed to be addressed as spiritual concerns. They were simply "political" or "social" concerns. And everyone knows the church shouldn't be involved in worldly concerns.

Douglas John Hall, the Canadian theologian, writes: "For centuries the church has presented its message largely as a variation on the following theme: If you believe in Jesus and do the right things here on earth, then you will be rewarded in eternity. The whole thrust of the thing is in the last clause. What transpires here on earth is at best a prelude to the real thing; more often it's a shabby sort of scene that has to be endured, or a testing-ground full of tricky temptations, or a brief and brutal episode preliminary to peace at the last (if you're good!). The wise will shut their eyes and grit their teeth and rein in their passions and do good…while there is yet time." Douglas John Hall, Christian Mission: The Stewardship of Life in the Kingdom of Death (New York: Friendship Press, 1985, p. 101.)

Everyone knows "the poor you will have with you always," and there will be "wars and rumors of war until the end of time." Concern for world peace will never be restored until Jesus comes back. To my knowledge, no one has ever thought to say: Well, sin will be with us 'til Jesus comes back, so what's the point in confronting it?

By and large, both conservative and liberal congregations share this characteristic in common: Both have very limited capacity to bring justice and peace concerns into the purview of biblical faith. Neither is able to imagine that spiritual integrity is at stake in the destruction of creation. When the church postpones fleshly redemption—the work of justice, of liberation—until the Second Coming of the messiah, it flatly ignores both the Old and New Testament descriptions of the messiah's work in history. In Scripture, the end of tyranny is inaugurated with the birth of the Anointed One. {Thomas D. Hanks, God So Loved the Third World, p. 10} To postpone that work to some "spiritualized" future unravels the very fabric of biblical promise and hope.

Horses, houses and human hearts

The third confusion which invariably cripples our notion of spiritual formation involves the connection between giving our hearts to Jesus and the way the world is presently ordered. One way to clarify this confusion, let’s look at how Scripture speaks of horses, houses and human hearts.

The Bible has two different pivotal images or metaphors for material reality—horses and houses.

For ancient Israel, "horses" represented military might and prowess. One could even say that horses were as strategically important in ancient times as tanks were in World War II. Time after time Israel was seduced away from trust in Yahweh God to a national policy of "peace through strength."

For example, Isaiah warns: "Woe to those who go down to Egypt for help and rely on horses, who trust in chariots, but do not look to the Holy One of Israel" (31:1). The Psalmist cautions: "Some boast of chariots, and some of horses; but we boast of the name of the Lord our God" (20:7). Hosea gives this word from the Lord: "But I will have pity on the house of Judah, and I will deliver them by the Lord their God; I will not deliver them by bow, nor by sword, not by war, not by horses, not by horsemen" (1:7).

It might be appropriate for us to paraphrase the text using terms more intelligible to modern ears: "I will not deliver them by Trident submarines, nor by Cruise or Pershing missiles, nor by policies of deterrence, massive arms buildups and covert operations, not even by Strategic Defense Initiatives."

Where "horses" for Israel represented military readiness, "houses" on the other hand was the metaphor for economic strength, for a robust domestic economy and an expanding foreign market, increased productivity and a larger Gross National Product. A few examples:

•Isaiah pronounces this verdict: ". . . and the Lord looked for justice, but behold, bloodshed; for righteousness, but behold a cry! Woe to those who join house to house, who add field to field, until there is no more room" (5:7-8).

•Amos makes this judgment: "Therefore because you trample upon the poor and take from them exactions of wheat, you have built houses of hewn stone, but you shall not dwell in them" (5:11).

•Matthew's gospel notes: "Woe to you, scribes and pharisees, hypocrites! For you devour widows' houses and for a pretense you make long prayers; therefore you will receive the greater condemnation" (23:14).

We should recall, too, that the premier and most concise biblical statement about idolatry (which is the issue of Scripture) is found in Jesus' utterance: "You cannot serve God and mammon" (Matthew 6:24; Luke 16:13). Mammon was not some first-century Palestinian deity competing with Yahweh God for the loyalty of the people. No, it is simply a word meaning wealth, power, status.

The third key biblical metaphor for this study is the word heart. In modern times, the heart is a metaphor for human emotions and sentiments, is the "romantic" organ and the most fickle of human organs.

In Hebrew thinking, however, the heart was the center of decision-making, the place where every individual factor—rationality, emotions, intuition, social tradition, etc.—flowed together. The heart was the Supreme Court, if you will, adjudicating the various claims of each of the separate factors and handing down a final, irrevocable decision. The heart represented the deepest level of a human personality. The Latin word credo, from which we get the word "creed," comes from two words which together mean "I give my heart to." Listen to these texts:

•Ezekiel gives voice to God's word: "And I will give them one heart, and put a new spirit within them; I will take the stony heart out of their flesh and give them a heart of flesh, that they may walk in my statutes and keep my ordinances" (11:19-20).

•The Psalmist sings: "It is well with those who deal generously and lend, who conduct their affairs with justice. They are not afraid of evil tidings; their hearts are firm, trusting in the Lord. Their hearts are steady, they will not be afraid" (112:5-9).

•Jeremiah predicts: "Behold the days are coming, says the Lord, when I will make a new covenant with the house of Israel.…I will put my law within them, and I will write it upon their hearts" (31:31-34).

•In Matthew, Jesus makes these striking claims: "Where your treasure is, there will your heart be also" (6:21).

•From the Acts of the Apostles: "Now the company of those who believed were of one heart and soul, and no one said that any of the things which they possessed were their own, but they had everything in common" (4:32).

The point of comparing these three biblical metaphors is to illustrate the fact that decisions about horses and houses are made in the human heart. The Kingdom of God is rightly said to be about human hearts, because it is in the human heart that choices are made about ultimate trust and security. Such decisions are not merely social, economic or political decisions. They are, at bottom, spiritual decisions. They are decisions about proper worship, about idolatry, about which god we will serve.

"Idolatry does not have to do with plastic pieces on dashboards but with ideological commitments which assign our deep loyalties to matters of vested interest. . . . The issue is not that we are nonbelievers but that our belief is assigned to unworthy and unworkable objects.…Such idolatries are misguided attempts to secure the city by trust in other gods because the terms of security from Yahweh are too costly." {Walter Brueggemann, Hopeful Imagination, p. 56}

In biblical terms, therefore, giving one's "heart" to Jesus is in fact the most subversive, world-threatening thing that can happen to a person. When it comes to matters of the heart, Jesus can never, ever be an absentee landlord. Indeed, listen to the most explicit “Christological” statement coming from Jesus’ own lips, when John the Baptist—then in prison, entertaining doubts about his earlier confirmation of Jesus’ identity—sends his disciples to ask if Jesus really is the Anointed of God. Jesus responds: “Go tell John what you hear and see: the blind receive sight and the lame walk, lepers are cleansed and the deaf hear; the dead are raised up and the poor have good news preached to them” (Matt. 11:4-5).

The healing of creation and the revealing of God’s purposes are inseparable. God’s plan of creation is never to be ripped from God’s plan of redemption. When the gratuitous love of God grips our hearts it creates its own momentum, prompting the gratuitous love for our neighbors. The proper acknowledgement for those who have no merited claim on Christ’ compassion is to mirror such compassion on behalf of those who have no merited claim on us. As St. Augustine said: “We imitate whom we adore.”

Let me close with what I consider a good attempt to restate in modern language Scripture’s call for the missionary mandate of healing and revealing:

As we enter this new millennium we reaffirm our abiding conviction that the God of Scripture manifests special concern for the cries of the poor—of the marginalized, the outcast, indeed all who have no access to the table. Correspondingly, we also believe that if the people of God are to be faithful to our calling we will locate ourselves in compassionate proximity to those whose lives are battered, bruised and broken. We do so not as an ethical demand or a work of righteousness but as a spiritual discipline. For we believe that God’s presence and voice are most easily recognized and understood in situations where life has been abandoned and hope is in retreat, where death is on the prowl and despair rules.

On the edge of this new millennium we testify to the Spirit’s plea to the church and to the world: Disarm your hearts! Repent of your habits of violence and injustice; return to the One who bore you in mercy; rebuild ruined neighborhoods; restore marginalized peoples; resume the politics of forgiveness and an economy of manna (sufficiency); revive an ecological relationship with the created order; reject the escalating culture of violence and renew your commitment to building a culture of peace.” (Excerpted from the “Open Letter to the 18th Baptist World Congress” statement of the fourth international Baptist peace conference, 2-4 January 2000, Melbourne, Australia.)

Sing with me the second stanza from that great missionary hymn:

“We’ve a song to be sun to the nations, That shall lift their hearts to the Lord,

A song that shall conquer evil, And shatter the spear and sword, And shatter the spear and sword.

For the darkness shall turn to dawning, And the dawning to noonday bright,

And Christ’s great kingdom shall come on earth, The kingdom of love and light.”

Ken Sehested is executive director of the Baptist Peace Fellowship of North America and co-pastor of Circle of Mercy, a new congregation in Asheville, N.C.

# # #

Stories to remind us that buoyancy

Stories to remind us that buoyancy scratch.

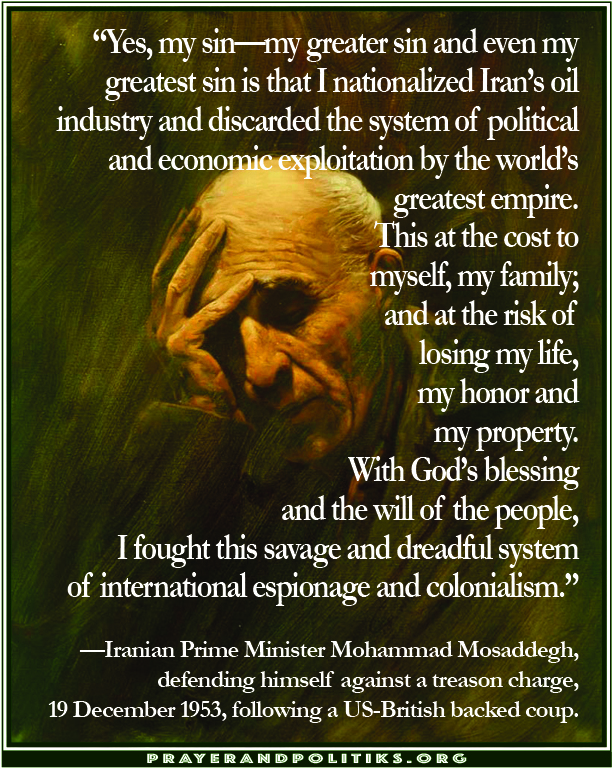

scratch. act of Congress) aimed at displacing the democratically elected Nicaraguan government.

act of Congress) aimed at displacing the democratically elected Nicaraguan government. are. . . . I’m not an apologize-for-America kind of guy.”

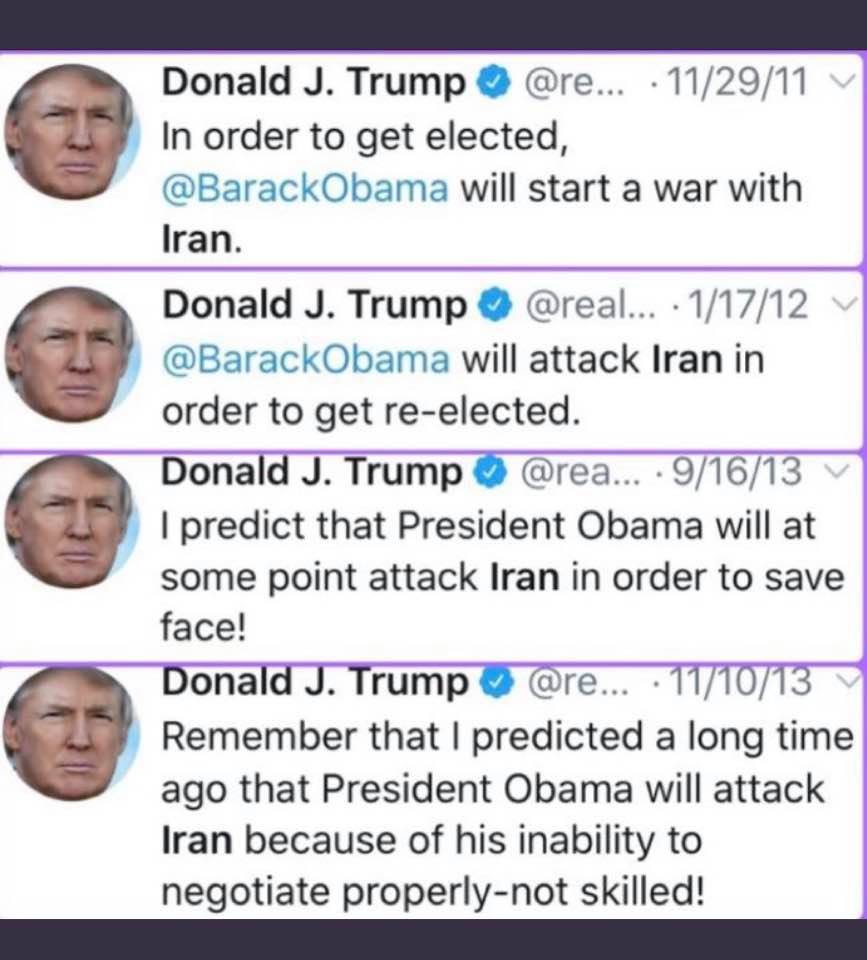

are. . . . I’m not an apologize-for-America kind of guy.” As I write, more than a dozen Iranian ballistic missiles have targeted two Iraqi military bases hosting US troops. It will be a long night, and likely more bloody tomorrows. The quote that first comes to mind is among the briefest: “Hatred bounces” (e.e. cummings).

As I write, more than a dozen Iranian ballistic missiles have targeted two Iraqi military bases hosting US troops. It will be a long night, and likely more bloody tomorrows. The quote that first comes to mind is among the briefest: “Hatred bounces” (e.e. cummings). Defending the action, US Admiral William Crowe, Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, “emphasized from the outset that committing military units to the Persian Gulf mission would involve risks and uncertainties.''

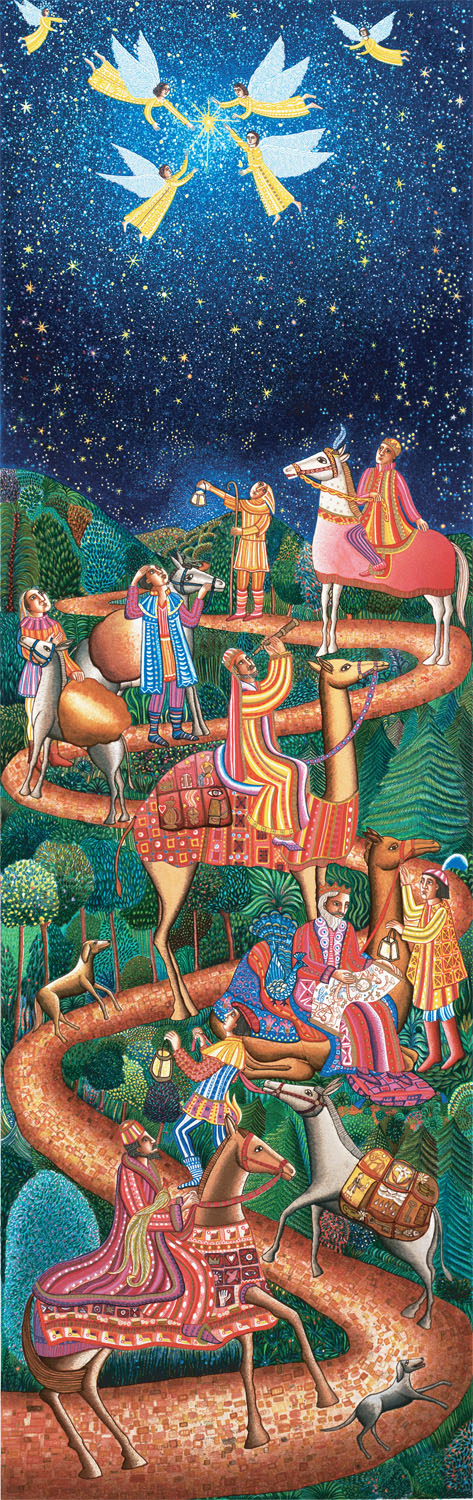

Defending the action, US Admiral William Crowe, Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, “emphasized from the outset that committing military units to the Persian Gulf mission would involve risks and uncertainties.'' There are three versions of what Epiphany (“Manifestation”) is meant to commemorate in the church’s calendar. One of those traditions is to celebrate Jesus’ baptism on January 6. Another tradition—Eastern Orthodox, using the Julian calendar—observes Christmas on January 7. Yet another tradition celebrates Epiphany as marking the arrival of the magi—of “We Three Kings” fame, the figures played in every Christmas play by children dressed in bathrobes. Yet the common element in each is the inauguration of a confrontation between God’s Only Begotten and those in seats of power.

There are three versions of what Epiphany (“Manifestation”) is meant to commemorate in the church’s calendar. One of those traditions is to celebrate Jesus’ baptism on January 6. Another tradition—Eastern Orthodox, using the Julian calendar—observes Christmas on January 7. Yet another tradition celebrates Epiphany as marking the arrival of the magi—of “We Three Kings” fame, the figures played in every Christmas play by children dressed in bathrobes. Yet the common element in each is the inauguration of a confrontation between God’s Only Begotten and those in seats of power.