Signs of the Times • 12 April 2021 • No. 212

¶ Invocation. With tonight’s setting sun, 1.9 billion Muslims around the world began observance of Ramadan, the month of special practices designed for spiritual renewal. Let us ask them to pray for the people of the United States, for we as a people believe that history’s shape and consummation is assured by the barrel of a gun.

¶ Call to worship. “The Adhan,” the call to prayer in Islam, performed by Hassen Rasool, a muezzin (a man who calls Muslims to prayer from the minaret of a mosque) in the United Kingdom.

Ramadan: A bit of background

Ramadan is a month of spiritual renewal, marked by daylight fasting, commemorating the revelation of the Qur’an, Islam’s scripture, to the Prophet Mohammad.

I confess a certain ambivalence in highlighting holy seasons of any special religious observance, because the public  practice of piety so often overlaps with the outbreak of violence. Indeed, the first mention of religious ritual in Hebrew Scripture, the respective “offerings to the Lord” by Cain and Abel (whose story is contained not only in Jewish and Christian Scripture, but also in the Qur’an), was also the occasion of the first murder (cf. Genesis 5).

practice of piety so often overlaps with the outbreak of violence. Indeed, the first mention of religious ritual in Hebrew Scripture, the respective “offerings to the Lord” by Cain and Abel (whose story is contained not only in Jewish and Christian Scripture, but also in the Qur’an), was also the occasion of the first murder (cf. Genesis 5).

Secularists are right to point out the frequent coincidence between religious devotion and human bloodshed.

But not right enough. Given the fact that violence is often justified by claims of transcendent and redemptive purposes, the most effective challenge to this coincidence should be mounted by interfaith coalitions committed to delegitimizing violence done in God’s name.

For more on that see “The things that make for peace: The purpose, promise and peril of interfaith engagement.”

For a little more background about Ramadan:

• Here is a short overview of the tradition and practices of Ramadan.

• “Six questions on Ramadan answered,” by Mohammad Hassan Khalil, is a very helpful and brief primer on Islam’s major annual observance. Religion News Service.

• Ramadan is observed during the ninth month of the Islamic calendar and is observed by Muslims worldwide as a month of fasting (Sawm) to commemorate the first revelation of the Quran to Muhammad according to Islamic belief. This annual observance is regarded as one of the Five Pillars of Islam. The month lasts 29–30 days based on the visual sightings of the crescent moon. —Wikipedia

• One way to practice interfaith understanding might be learning to pronounce a traditional greeting in Arabic: "As-salamu alaikum," which translates “Peace be upon you”; and the traditional response: “Wa alaykumu as-salam,” or “And unto you peace.” Here is one very brief aid in pronouncing of these two phrases. (Transliteration Arabic into English results in a variety spellings.)

• For more on the commonalities in peacemaking traditions among Jews, Christians, and Muslims, see “Peace Primer II: Quotes from Jewish, Christian, and Islamic Scripture & Tradition.”

§ § §

¶ “Erev Shel Shoshanim” (“Evening of Lilies [or Roses”]) by Yuval Ron Ensemble. This song, a love song well known throughout the Middle East, is dedicated to the children of Jerusalem, the vision of peace between Jews and Arabs, and peace around the world.

§ § §

Last week I received an Associated Church Press award for the following short story.

A Broadman Hymnal story

The story begins on a Saturday, before dawn, while still in high school. I began my 12-hour shift of pumping gas, doing oil changes, and washing cars in my hometown along the South Louisiana bayous.

First thing when we opened was to transfer product displays and stacks of new tires outside. The radio was on—the  station owner loved the Cajun and Zydeco music on the local station. Then the music stopped, momentarily, for a bit of news. The announcer was saying something about Martin Luther King Jr.

station owner loved the Cajun and Zydeco music on the local station. Then the music stopped, momentarily, for a bit of news. The announcer was saying something about Martin Luther King Jr.

“That Martin Luther Coon, he ain’t no Christian,” Mr. Dediveaux muttered toward the radio in an emphatically derogatory tone. “Everywhere he go there’s trouble.”

It would be years before it occurred to me the same was likely said about Jesus.

As the product of a piety-saturated, apolitical religious environment (except when liquor and gambling policies were on the electoral ballot), I was largely oblivious to the Civil Rights Movement. But by the time I entered seminary, the history and figures of the era became an obsession. I read everything I could get my hands on.

One of my purchases was an oversized book filled with photos of Dr. King and a host of other movement luminaries. To this day I retain the vivid memory of being caught up in a bewildering epiphany as I turned from one page to the next. As if my gut had goosebumps.

It took me a few seconds to comprehend the prophetic disclosure that unfolded. The photo was of Martin Luther King Jr. and his wife Coretta sitting at a piano, their infant daughter Yolanda perched on Martin’s lap, as he and Coretta sang from an open hymnal.

As my eyes began searching out the details, there it was. The hymnal cover was clear. It was the Broadman Hymnal. The hymnal I grew up with. Published by the Southern Baptist Convention, a denomination that formed over the express conviction that even missionaries could own slaves.

At one time I could quote from memory the page number of dozens of titles in that hymnal. As I came to discover, a good many churches that hosted Civil Rights Movement mass meetings—churches that were threatened by cross-burning Klan torches—did their singing from the Broadman.

I also learned that terrorism on American soil has a long history.

That moment—that photo—stands among my life’s greatest revelations. I came to realize that the language of faith can have many different, even competing meanings, just as any chemical compound, minus even one element, turns into something else altogether.

My life’s preoccupation since then has been sorting out the redemptive notes from the enslaving.

§ § §

¶ “Christ is risen from the dead / Trampling down death by death / And to those in the tombs / Bestowing life!” —translated lyrics of “Christ Is Risien,” a Greek/Antiochian Orthodox Paschal troporian sung on Easter Sunday, by Fairouz

§ § §

An Easter Sunday meditation

Easter’s fertile promise: Composting as parable of faith formation

I’ve never had a green thumb. My wife tends indoor plants and outside flowers. I’ve never had the urge to garden, though I wish I had.

But I’ve enjoyed making dirt for over 30 years. Soil, I should say. Dark, fertile, nutrition rich soil that growing things need to thrive, filled with nitrogen, phosphorus, potassium, and a dozen other nutrients and organic matter.

I keep three compost stashes going. A two-gallon bucket next to the kitchen sink, where I deposit scraps from meal preparation, certain dinner leftovers, coffee grounds, napkins, and shredded paper. Once every week or so, when it’s full, I take it outside and empty it in a 96-gallon compost container, next to a mound of “brown” material—leaves and  grass clippings—for covering each deposit. I’m not in a hurry, so I don’t turn the compost, which would speed up the process; I just let the weather and worms do their work.

grass clippings—for covering each deposit. I’m not in a hurry, so I don’t turn the compost, which would speed up the process; I just let the weather and worms do their work.

Once each year I empty the composter and cover it with a layer of brown material, where it will sit, undisturbed. After “cooking” for a year, it’s ready to do its magic. So I shovel it into cardboard boxes, careful to remove the weed roots that encroached over the past year. The load comes to about a half-yard, filling my pickup bed for transport to our kiddos’ house up the street. My son-in-law, Rich, tends a large garden. It’s down payment for a bountiful harvest of vegetables and berries to come.

This is my substitute for an Easter sunrise service. (I’m not an early riser.)

Most of the brown material comes from my own yard. But if the leaf harvest in late fall is smaller than normal, I’ll patrol my neighborhood streets and collect bagged leaves set out for the city to pick up.

Composting isn’t hard, but it’s not convenient, either. It takes some work and persistent attention.

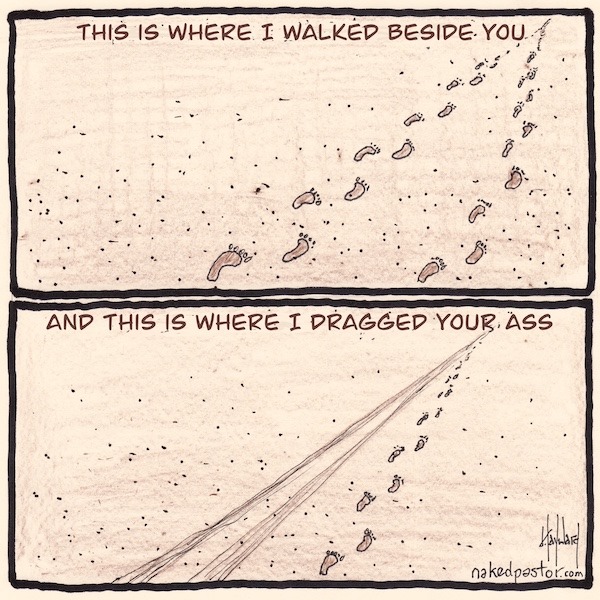

Sometimes the labor of spiritual formation is, in fact, hard. Grace sometimes takes us to places we would otherwise not be inclined to go; or be with people we’d otherwise avoid; or pay attention to news that we’d just as soon ignore.

Sometimes spiritual growth is like an earthquake, unsettling things we thought would always be certain and secured. Sometimes it's a big screen drama, brimming with a scary storyline, and heroic gestures and heart-pounding action, with valor in the dark and near-catastrophes and undeserved affliction.

All the saints have scars and bruises and limps and even missing limbs. All had, like us, scrap material: peelings, bruised spots, wilted and other gone-bad produce, indigestible trimmings, rinds and seeds. The promise of compost, like Easter, is that nothing is wasted. Part of resurrection’s exultation is knowing God wants all of us. In one of his poems, Steve Garnaas-Holmes has this striking metaphor, “God licks the spoon of us.”

Spiritual formation can be wearisome, can place you in a storm-tossed boat, can demand more than you think you can bear. It is almost never convenient and can be unnerving. It is not risk-averse.

But most of the time, spiritual formation is much like composting. It requires persistent attention, intentional choices,  and locating yourself in a community where some bring nitrogen, some phosphorous, some potassium and the like. Mostly there are no fireworks or theatrics, much less headline news, and almost never fame nor fortune.

and locating yourself in a community where some bring nitrogen, some phosphorous, some potassium and the like. Mostly there are no fireworks or theatrics, much less headline news, and almost never fame nor fortune.

Spiritual formation is quotidian work. In ordinary circumstances. Sweating the small stuff; showing up; giving attention, without the need for billboards, to the needs on the streets whose names you know. It requires constructing a custom-made rhythm of work and rest; of action and reflection; of listening and speaking; and making a nest with others—ordinary, non-saintly, sometimes eccentric others—who are attempting the same.

Left: Easter Sunday flowered cross, Milagro Christian Church, Boulder, CO. Photo by Marnie Leinberger.

There is work to be done (not to mention merriment and sweet treats). But sustainability is not ours to engineer. There is a fecund Presence in Creation we can count on.

Dominion is not up to us. But cultivating is. Don’t mind the sweat and don’t neglect your gloves; but don’t postpone joy.

As Gerard Manley Hopkins wrote, in his say-it-slant way, God longs to “easter in us.” Join your will to that Way.

Ken Sehested, Easter Sunday, 4 April 2021

§ § §

¶ Benediction. “Tala' al-Badru Alayna” (“White Moon”),” which many believe to be the oldest known Islamic song, welcoming the Prophet Muhammad and his companions as they sought refuge in Medina. —Abraham Jam

# # #

©Ken Sehested @ prayerandpolitiks.org. Language not otherwise indicated above is that of the editor, as are those portions cited as “kls.” Don’t let the “copyright” notice keep you from circulating material you find here (and elsewhere in this site). Reprint permission is hereby granted in advance for noncommercial purposes.

Feel free to copy and post any original art on this site. (The ones with “prayerandpolitiks.org” at the bottom.) As well as other information you find helpful.

Your comments are always welcomed. If you have news, views, notes or quotes to add to the list above, please do. If you like what you read, pass this along to your friends. You can reach me directly at kensehested@prayerandpolitiks.org.

the Lamb of God.” —“

the Lamb of God.” —“ God, full of compassion, Who dwells on high, grant true rest upon the wings of the Shechinah, in the exalted spheres of the holy and pure, who shine as the resplendence of the firmament, to the souls of Victims of September 11th who [have] gone to their eternal home; may their place of rest be in Gan Eden.” —translated lyrics of Jewish Cantor Azi Schwartz singing “

God, full of compassion, Who dwells on high, grant true rest upon the wings of the Shechinah, in the exalted spheres of the holy and pure, who shine as the resplendence of the firmament, to the souls of Victims of September 11th who [have] gone to their eternal home; may their place of rest be in Gan Eden.” —translated lyrics of Jewish Cantor Azi Schwartz singing “ Born to Die),” Doc Watson and Gaither Carlton

Born to Die),” Doc Watson and Gaither Carlton

breaks, and earth’s vain shadows flee / In life, in death, o Lord, abide with me / Abide with me, abide with me.” —“

breaks, and earth’s vain shadows flee / In life, in death, o Lord, abide with me / Abide with me, abide with me.” —“

Some of China’s blame, for delaying news of the pandemic’s spread, is merited. Then again,

Some of China’s blame, for delaying news of the pandemic’s spread, is merited. Then again,  By the middle of the 20th century, these two factors—a significant population of objectors to China’s ruling Communist Party, along with Hong Kong’s booming economy—created a

By the middle of the 20th century, these two factors—a significant population of objectors to China’s ruling Communist Party, along with Hong Kong’s booming economy—created a  about the state of our sin sick soul as anyone I know.

about the state of our sin sick soul as anyone I know. empowering. It was as if we were able to put a bridle on our sorrow and anger and frustration to guide and hasten our journeys. Such is the goal of lament’s proper work.

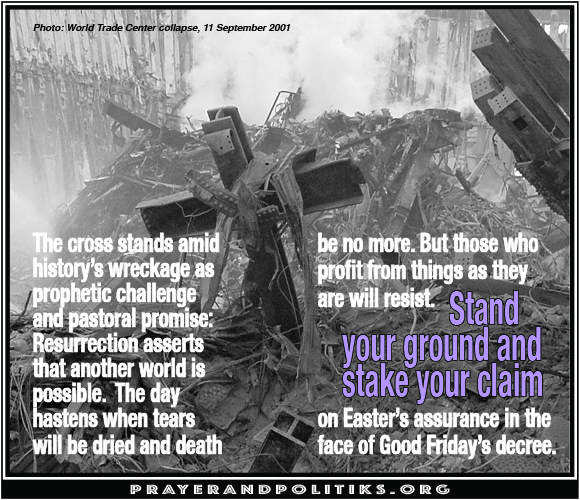

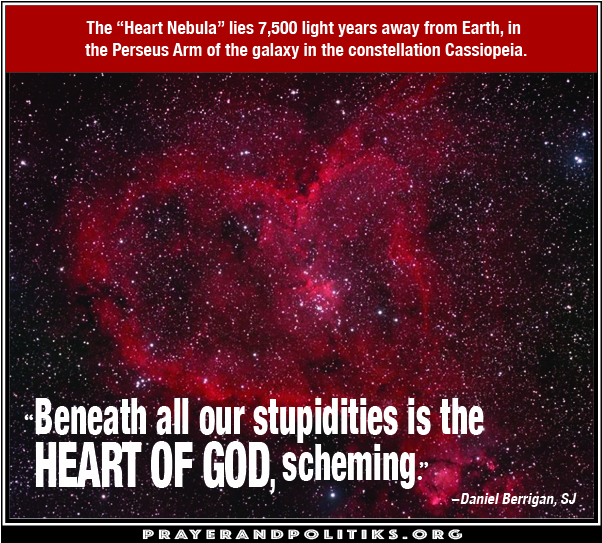

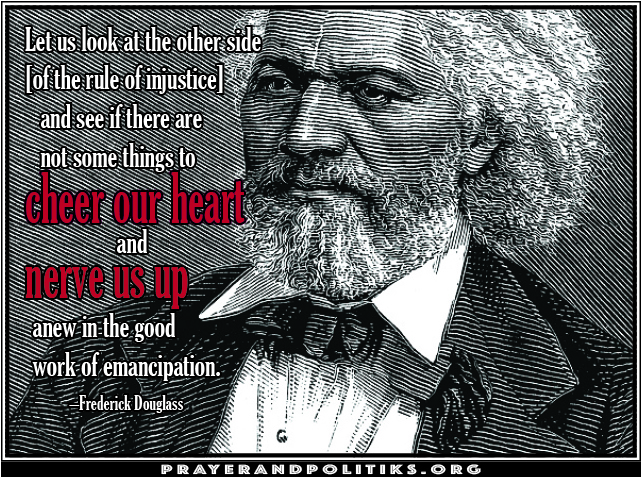

empowering. It was as if we were able to put a bridle on our sorrow and anger and frustration to guide and hasten our journeys. Such is the goal of lament’s proper work. So we continue scheming (see the art at top) together, anticipating the day when hope and history align. And we “

So we continue scheming (see the art at top) together, anticipating the day when hope and history align. And we “ several members of the congregation to offer a faith story during worship, talking about how their faith influenced their workaday decisions. Tom was among those.

several members of the congregation to offer a faith story during worship, talking about how their faith influenced their workaday decisions. Tom was among those. collaborated in arranging Shabazz’s murder—is raising the investigative stakes. (For more on this see

collaborated in arranging Shabazz’s murder—is raising the investigative stakes. (For more on this see  has held up reasonably well, given recent history, particularly with the mobilizing work of Black Lives Matter and the renewed controversy over US history in light of repeated incidents of the killings of unarmed Black folk.

has held up reasonably well, given recent history, particularly with the mobilizing work of Black Lives Matter and the renewed controversy over US history in light of repeated incidents of the killings of unarmed Black folk. the voice of Malcolm X, among the most prophetic voices in our nation’s history. His breath of fire is not for our incineration but for our refinement. We submit to it not because we long for punishment but because we have been captivated by a dream as big as God.

the voice of Malcolm X, among the most prophetic voices in our nation’s history. His breath of fire is not for our incineration but for our refinement. We submit to it not because we long for punishment but because we have been captivated by a dream as big as God. better. Then when you know better, do better.”

better. Then when you know better, do better.” name on it.

name on it.

sometimes it’s hard for the heart to hear from

sometimes it’s hard for the heart to hear from a room full of us, members of the Iraq Peace Team, who had carried on a constant presence in Baghdad for more than seven years. I had led in the last group of short-term volunteers, arriving in the second week of February.

a room full of us, members of the Iraq Peace Team, who had carried on a constant presence in Baghdad for more than seven years. I had led in the last group of short-term volunteers, arriving in the second week of February. Donald Trump, MSN

Donald Trump, MSN  Club rum, and everyone gets tipsy, and the ice

Club rum, and everyone gets tipsy, and the ice