§ It may be true that every prophet is a pain in the neck, but it is not true that every pain in the neck is a prophet. There is no more firmly entrenched expression of the false self than the self-proclaimed prophet.

§ It may be true that every prophet is a pain in the neck, but it is not true that every pain in the neck is a prophet. There is no more firmly entrenched expression of the false self than the self-proclaimed prophet.

§ The twofold weakness of the Augustinian [just war] theory is its stress on a subjective purity of intention which can be doctored and manipulated with apparent “sincerity” and the tendency to pessimism about human nature and the world, now used as a justification for recourse to violence.

§ While we learn to be humble and virtuous as individuals, we allow ourselves to commit the worst crimes in the name of "society." We are gentle in our private life in order to be murderers as a collective group. For murder, committed by an individual, is a great crime. But when it becomes war or revolution, it is represented as the summit of heroism and virtue.

§ In the old days, on Easter night, the Russian peasants used to carry the blest fire home from church. The light would scatter and travel in all directions through the darkness, and the desolation of the night would be pierced and dispelled as lamps came on in the windows of the farm houses, one by one. Even so the glory of God sleeps everywhere, ready to blaze out unexpectedly in created things. Even so God’s peace and order lie hidden in the world, even the world of today, ready to reestablish themselves, in God’s own good time: but never without the instrumentality of free options made by free people.

§ True contemplation is not a psychological trick but a theological grace. It can come to us only as a gift, and not as a result of our own clever use of spiritual techniques.

§ The real freedom is the freedom to be able to come and go from that center (essence of you, spark of the soul), and to be able to do without anything that is not immediately connected to that center. Because when we die, everything is destroyed except this one thing, which is our reality and which is the reality that God preserves forever.

§ The real freedom is the freedom to be able to come and go from that center (essence of you, spark of the soul), and to be able to do without anything that is not immediately connected to that center. Because when we die, everything is destroyed except this one thing, which is our reality and which is the reality that God preserves forever.

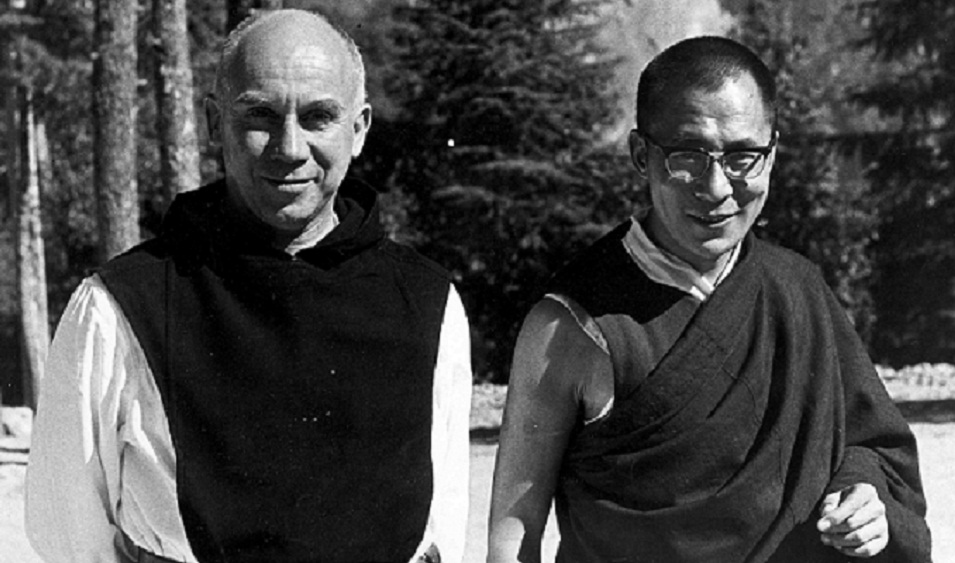

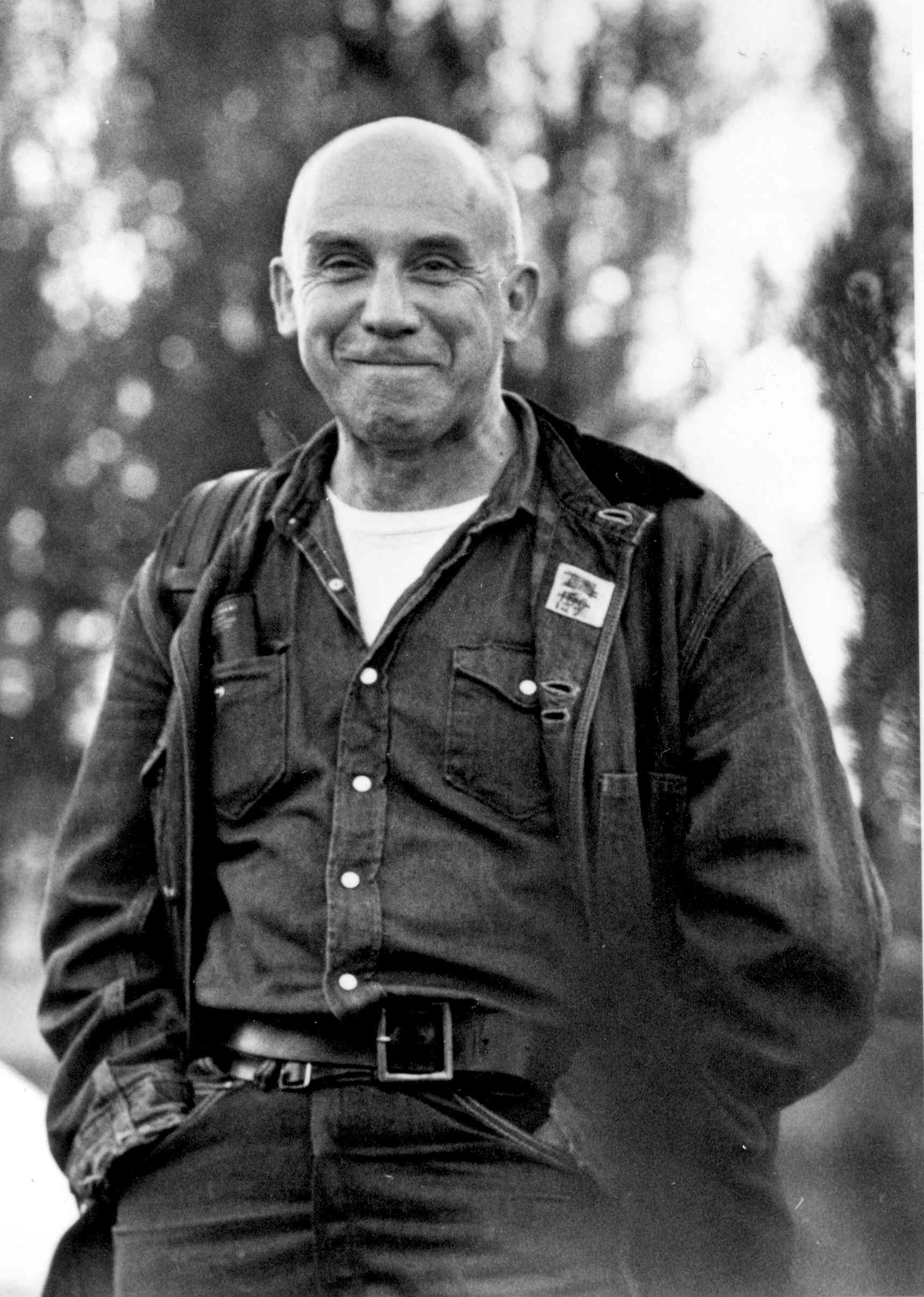

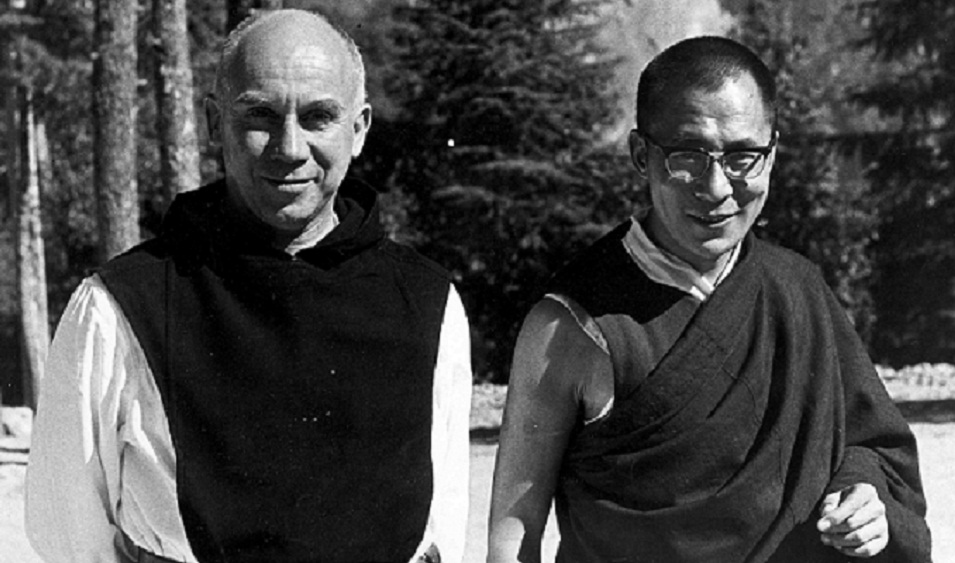

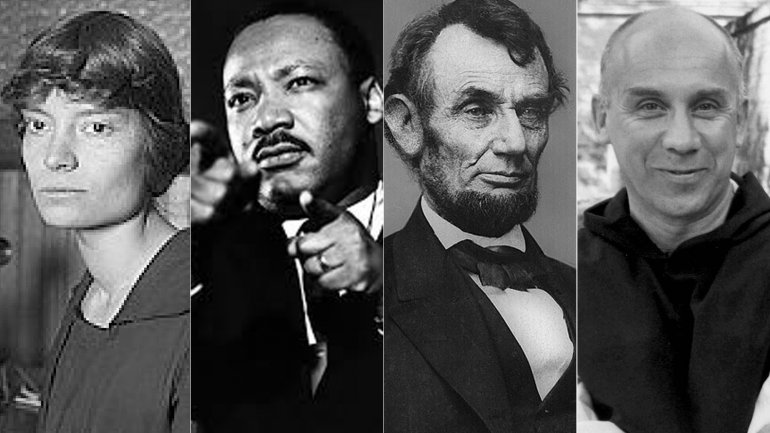

Left: Merton with the Dalai Lama, 1968

§ In the spiritual life there is no such thing as indifference to love or hate. That is why tepidity (which seems to be indifferent) is so detestable. It is hate disguised as love.

§ Place no hope in the inspirational preachers of Christian sunshine, who are able to pick you up and set you back on your feet and make you feel good for three or four days—until you fold up and collapse into despair.

§ That is why pilgrimage is necessary, in some shape or other. Mere sitting at home and meditating on the divine presence is not enough for our time. We have to come to the end of a long journey and see that each stranger we meet there is no other than ourselves—which is the same as saying we find Christ in them.

§ I am sick up to the teeth and beyond the teeth, up to the eyes and beyond the eyes, with all forms of projects and expectations and statements and programs and explanations of anything, especially explanations about where we are all going, because where we are all going is where we went a long time ago, over the falls. We are in a new river and we don’t know it.

§ I am sick up to the teeth and beyond the teeth, up to the eyes and beyond the eyes, with all forms of projects and expectations and statements and programs and explanations of anything, especially explanations about where we are all going, because where we are all going is where we went a long time ago, over the falls. We are in a new river and we don’t know it.

§ The real focus of American violence is not in esoteric groups but in the very culture itself, its mass media, its extreme individualism and competitiveness, its inflated myths of virility and toughness, and its overwhelming preoccupation with the power of nuclear, chemical, bacteriological, and psychological overkill. If we live in what is essentially a culture of overkill, how can we be surprised at finding violence in it?

§ God does not give divine joy to us for ourselves alone, and if we could possess God for ourselves alone we would not possess God at all. Any joy that does not overflow from our souls and help others to rejoice in God does not come to us from God.

§ Propaganda makes up our minds for us, but in such a way that it leaves us the sense of pride and satisfaction of those who have made up their own minds. And in the last analysis, propaganda achieves this effect because we want it to.

§ Few of us have actively and consciously chosen to oppress and mistreat the Negro. But nevertheless we have all more or less acquiesced in and consented to a state of affairs in which the Negro is treated unjustly, and in which his unjust treatment is directly or indirectly to the advantage of people like ourselves.

§ For [French theologian Gabriel] Vahanian, biblical religion shows us once for all that humankind’s basic obligation to God is iconoclasm. That sounds wild, but it is only a reformulation of the first two [of the 10] commandments.

§ Life is not to be regarded as an uninterrupted flow of words which is finally silenced by death. Its rhythm develops in silence, comes to the surface in moments of necessary expression, returns to deeper silence, culminates in a final  declaration, then ascends quietly into the silence of Heaven which resounds with unending praise.

declaration, then ascends quietly into the silence of Heaven which resounds with unending praise.

§ You do not need to know precisely what is happening, or exactly where it is all going. What you need is to recognize the possibilities and challenges offered by the present moment, and to embrace them with courage, faith and hope.

§ Too ardent a desire for contemplation can be an obstacle to contemplation, because it may proceed from delusion and attachment to one’s self.

§ You cannot be a person of faith unless you know how to doubt. You cannot believe in God unless you are capable of questioning the authority of prejudice, even though that prejudice may seem to be religious.

§ God utters me like a word containing a partial thought of God’s own Self.

§ To work out our own identity in God, which the Bible calls “working out our salvation,” is a labor that requires sacrifice and anguish, risk and many tears.

§ People may spend their whole lives climbing the ladder of success only to find, once they reach the top, that the ladder is leaning against the wrong wall.

§ It’s a risky thing to pray, and the danger is that our very prayers get between God and us. The great thing in prayer is not to pray, but to go directly to God. If saying your prayers is an obstacle to prayer, cut it out. The best way to pray is: stop. Let prayer pray within you, whether you know it or not. This means a deep awareness of our true inner identity. It implies a life of faith, but also of doubt. You can’t have faith without doubt. Give up the business of suppressing doubt. Doubt and faith are two sides of the same thing. Faith will grow out of doubt, the real doubt. We don’t pray right because we evade doubt. And we evade it by regularity and by activism. It is in these two ways that we create a false identity, and these are also the two ways by which we justify the self-perpetuation of our institutions.

§ It is the love of my lover, my neighbor or my child that sees God in me, makes God credible to myself in me. And it is my love for my lover, my child, my neighbor, that enables me to show God to each.

§ It is the love of my lover, my neighbor or my child that sees God in me, makes God credible to myself in me. And it is my love for my lover, my child, my neighbor, that enables me to show God to each.

§ When protest simply becomes an act of desperation, it loses its power to communicate anything to anyone who does not share the same feelings of despair.

§ Pride makes us artificial and humility makes us real.

§ The tighter you squeeze, the less you have.

§ Love is our true identity. We do not find the meaning of life by ourselves along—we find it with another.

§ To consider persons and events and situations only in the light of their effect upon myself is to live on the doorstep of hell.

§ The racial crisis in the US has rightly been diagnosed as a “colonial crisis” with the country itself.

§ “Freedom” cannot retain its meaning if it continues to be only freedom for some based on violent repression of others.

§ We live in a society that tries to keep us dazzled with euphoria in a bright cloud of lively and joy-loving slogans. Yet nothing is more empty and more dead, nothing is more insultingly insincere and destructive than the vapid grins on the billboards and the moron beatitude in the magazines which assure that we are all in bliss right now.

§ If for some reason it were necessary for you to drink a pint of water taken out of the Mississippi River and you could choose where it was to be drawn out of the river—would you take a pint from the source of the river in Minnesota or from the estuary in New Orleans?

§ Quoting Simone Weil: What is called national security is a chimerical state of things in which one would keep for oneself  alone the power to make war while all other countries would be unable to do so. . . . War is therefore made in order to keep or to increase the means of making war. All international politics revolve in this vicious circle.

alone the power to make war while all other countries would be unable to do so. . . . War is therefore made in order to keep or to increase the means of making war. All international politics revolve in this vicious circle.

§ In Vietnam the US has officially adopted the policy that the best way to get across an idea is by fire and dynamite.

§ The whole idea of compassion is based on a keen awareness of the interdependence of all these living beings, which are all part of one another, and all involved in one another.

§ Happiness is not a matter of intensity but of balance, order, rhythm and harmony.

§ The Gospel is handed down from generation to generation but it must reach each one of us brand new, or not at all. If it is merely "tradition" and not news, it has not been preached or not heard—it is not Gospel. . . . If there is no risk in revelation, if there is no fear in it, if there is no challenge in it, if it is not a word which creates whole new worlds, and new beings, if it does not call into existence a new creature, our new self, then religion is dead and God is dead.

§ And though the age is confused, it is no sin for us to be nevertheless happy and to have hopes, provided they are not the vain and empty hopes of a world that is merely affluent.

§ In order to find God in ourselves, we must stop looking at ourselves, stop checking and verifying ourselves in the mirror of our own futility, and be content to be in God and to do whatever God wills, according to our limitations, judging our acts not in the light of our own illusions, but in the light of God’s reality which is all around us in the things and people we live with.

§ I can come up with no better choice than to listen very seriously to the Negro, and what they have to say. I, for one, am absolutely ready to believe that we need them to be free, for our sake even more than for their own.

§ Prayers and sacrifice must be used as the most effective spiritual weapons in the war against war, and like all weapons they must be used with deliberate aim: not just with a vague aspiration for peace and security, but against violence and against war. This implies that we are also willing to sacrifice and restrain our own instinct for violence and aggressiveness in our relations with other people. We may never succeed in this campaign, but whether we succeed or not, the duty is evident. It is the great Christian task of our time. Everything else is secondary, for the survival of the human race itself depends upon it.

§ Prayers and sacrifice must be used as the most effective spiritual weapons in the war against war, and like all weapons they must be used with deliberate aim: not just with a vague aspiration for peace and security, but against violence and against war. This implies that we are also willing to sacrifice and restrain our own instinct for violence and aggressiveness in our relations with other people. We may never succeed in this campaign, but whether we succeed or not, the duty is evident. It is the great Christian task of our time. Everything else is secondary, for the survival of the human race itself depends upon it.

§ Those who know nothing of God and whose lives are centered on themselves, imagine that they can only find themselves by asserting their own desires and ambitions and appetites in a struggle with the rest of the world. They try to become real by imposing themselves on others, by appropriating for themselves some share of the limited supply of created goods and thus emphasizing the difference between themselves and others who have less than they, or nothing at all.

§ We have to recognize that a spirit of individualism and confusion has reduced us to an ethic of “every man for himself and the devil take the hindmost.” This ethic, unfortunately sometimes consecrated by Christian formulas, is nothing but the secular ethic of the affluent society, based on the false assumption that if everyone is bent on making money for themselves the common good will automatically follow, due to the operation of economic laws.

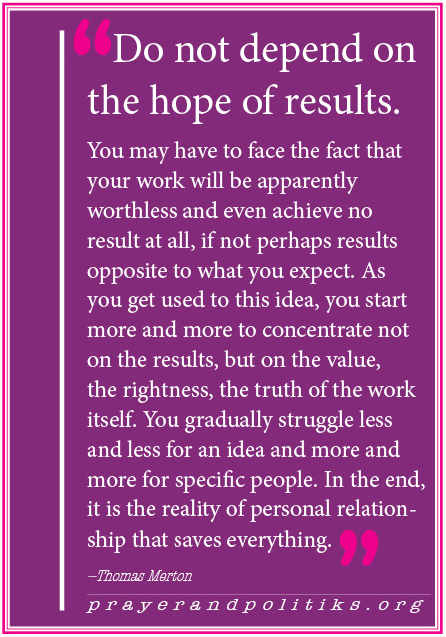

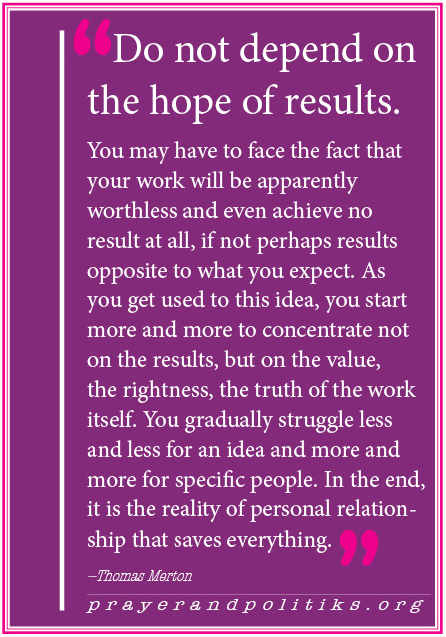

§ The life of contemplation in action and purity of heart is, then, a life of great simplicity and inner liberty. One is not seeking anything special or demanding any particular satisfaction. One is content with what is. One does what is to be done, and the  more concrete it is, the better. One is not worried about the results of what is done. One is content to have good motives and not too anxious about making mistakes. In this way one can swim with the living stream of life and remain at every moment in contact with God, in the hiddenness and ordinariness of the present moment with its obvious task.

more concrete it is, the better. One is not worried about the results of what is done. One is content to have good motives and not too anxious about making mistakes. In this way one can swim with the living stream of life and remain at every moment in contact with God, in the hiddenness and ordinariness of the present moment with its obvious task.

§ The truth that many people never understand, until it is too late, is that the more you try to avoid suffering the more you suffer because smaller and more insignificant things begin to torture you in proportion to your fear of being hurt.

§ If I insist on giving you my truth, and never stop to receive your truth in return, then there can be no truth between us.

§ What is the place of Christians in all this? Do simply to fold our hands and resign ourselves to the worst, accepting it as the inescapable will of God and preparing ourselves to enter heaven with a sigh of relief? Should we open up the apocalypse and run out into the street to give everyone our ideas of what is happening? Or worse still, should we take a hard-headed and "practical" attitude about it and join in the madness of the warmakers, calculating how by a "first strike," the glorious Christian West can eliminate atheistic communism for all time and usher in the millennium? . . . I am no prophet and no seer but it seems to me that this last position may very well be the most diabolical of illusions, the great and not even subtle temptation of a Christianity that has grown rich and comfortable, and is satisfied with its riches.  What are we to do? The duty of Christians in this crisis is to strive with all our power and intelligence, with our faith, hope in Christ, and love for God and humankind, to do the one task which God has imposed upon us in the world today. That task is to work for total abolition of war.

What are we to do? The duty of Christians in this crisis is to strive with all our power and intelligence, with our faith, hope in Christ, and love for God and humankind, to do the one task which God has imposed upon us in the world today. That task is to work for total abolition of war.

§ What we have to be is what we are.

§ Merely accepted, suffering does nothing for our souls except, perhaps, to harden them. Endurance alone is no consecration. True asceticism is not a mere cult of fortitude. We can deny ourselves rigorously for the wrong reason and end up by pleasing ourselves mightily with our self-denial.

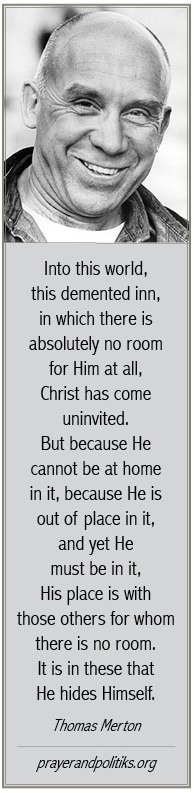

§ Into this world, this demented inn, in which there is absolutely no room for Him at all, Christ has come uninvited. But because He cannot be at home in it, because He is out of place in it, His place is with those others for whom there is no room. His place is with those who do not belong, who are rejected by power because they are regarded as weak, those who are discredited, who are denied the status of persons, who are tortured, bombed, and exterminated. With those for whom there is no room, Christ is present in the world. He is mysteriously present in those for whom there seems to be nothing but the world at its worst. . . It is in these that Christ hides, for whom there is no room.

§ When you expect the world to end at any moment, you know there is no need to hurry. You take your time, you do your work well.

§ Nonviolence must simply avoid the ambiguity of an unclear and confusing protest that hardens the warmakers in their self-righteous blindness. This means that in this case above all nonviolence must avoid a facile and fanatical  self-righteousness, and refrain from being satisfied with dramatic, self-justifying gestures. . . . Christian nonviolence . . . is convinced that the manner in which the conflict for truth is waged will itself manifest or obscure the truth.

self-righteousness, and refrain from being satisfied with dramatic, self-justifying gestures. . . . Christian nonviolence . . . is convinced that the manner in which the conflict for truth is waged will itself manifest or obscure the truth.

§ When ambition ends, happiness begins.

§ The whole meaning of the spiritual life is to be sought in love.

§ The great thing after all is to live, not to pour out your life in the service of a myth: and we turn the best things into myths. If you can get free from the domination of causes and just serve Christ's truth, you will be able to do more and will be less crushed by the inevitable disappointments. . . . The real hope, then, is not in something we think we can do, but in God who is making something good out of it in some way we cannot see. If we can do God’s will, we will be helping in this process. But we will not necessarily know all about it beforehand.

§ The grateful person knows that God is good, not by hearsay but by experience. And that is what makes all the difference

§ When I am liberated by silence, when I am no longer involved in the measurement of life, but in the living of it, I can discover a form of prayer in which there is effectively no distraction. My whole life becomes prayer.

§ Anxiety is the mark of spiritual insecurity.

§ When we are truly ourselves we lose most of the futile self-consciousness that keeps us constantly comparing ourselves with others in order to see how big we are.

§ We do not want to be beginners [at prayer]. But let us be convinced of the fact that we will never be anything but beginners, all our life!

§ Merely to resist evil with evil by hating those who hate us and seeking to destroy them, is actually no resistance at all. It is active and purposeful collaboration in evil that brings the Christian into direct and intimate contact with the same source of evil and hatred which inspires the acts of enemy. It leads in practice to a denial of Christ and to the service of hatred rather than love.

§ There is no wilderness so terrible, so beautiful, so arid and so fruitful as the wilderness of compassion. It is the only desert that shall truly flourish like the lily.

§ We have got to be aware of the awful sharpness of the truth when it is used as a weapon, and since it can be the deadliest weapon, we must take care that we don't kill more than falsehood with it. In fact we must be careful how we “use” truth, for we are ideally the instruments of truth and not the other way round.

§ Nonviolence seeks to "win" not by destroying or even by humiliating adversaries, but by convincing them that there is a higher and more certain common good than can be attained by bombs and blood.

§ What a relief it was for me, now, to discover not only that no idea of ours, let alone any image, could adequately represent God, but also that we should not allow ourselves to be satisfied with any such knowledge of God.

§ How crazy it is to be “yourself” by trying to live up to an image of yourself you have unconsciously created in the minds of others.

§ Yet the fact remains that we are invited to forget ourselves on purpose, cast our awful solemnity to the winds and join in the general dance.

§ If we are to love sincerely, and with simplicity, we must first of all overcome the fear of not being loved. And this cannot be done by forcing ourselves to believe in some illusion, saying that we are loved when we are not. We must somehow strip ourselves of our greatest illusions about ourselves, frankly recognize in how many ways we are unlovable, descend into the depths of our being until we come to the basic reality that is in us, and learn to see that we are lovable after all, in spite of everything!

§ It often happens, as a matter of fact, that so called “pious souls” take their “spiritual life” with a wrong kind of seriousness.

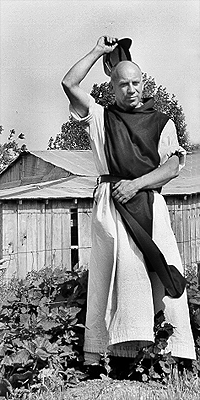

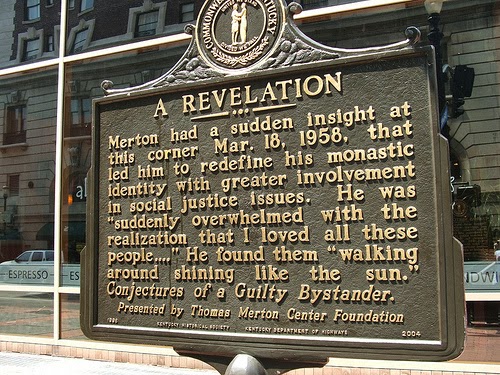

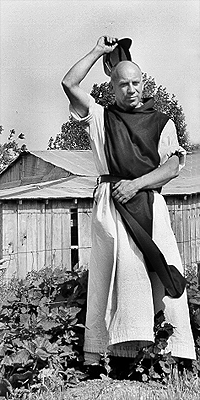

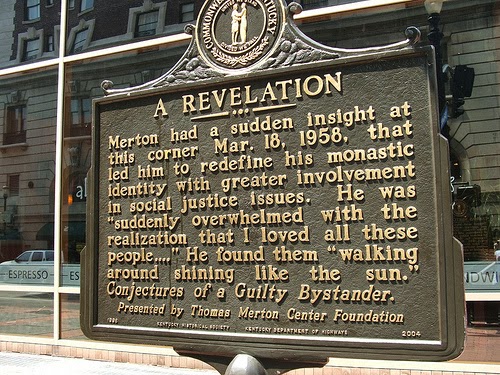

§ In March 1958, while in Louisville on Abbey business, Merton had an epiphany which would profoundly shape the rest of his life and dramatically reorient his understanding of contemplative life: In Louisville, at the corner of Fourth and Walnut, in  the center of the shopping district, I was suddenly overwhelmed with the realization that I loved all these people, that they were mine and I theirs, that we could not be alien to one another even though we were total strangers. It was like waking from a dream of separateness, of spurious self-isolation in a special world.

the center of the shopping district, I was suddenly overwhelmed with the realization that I loved all these people, that they were mine and I theirs, that we could not be alien to one another even though we were total strangers. It was like waking from a dream of separateness, of spurious self-isolation in a special world.

§ We must approach our meditation realizing that “grace,” “mercy,” and “faith” are not permanent inalienable possessions which we gain by our efforts and retain as though by right, provided that we behave ourselves. They are constantly renewed gifts

§ Contemplatives are not those who takes their prayer seriously, but who takes God seriously, those who are famished for truth, who seek to live in generous simplicity, in the spirit. An ardent and sincere humility is the best protection for the life of prayer.

§ There is always a temptation to diddle around in the contemplative life, making itsy-bitsy statues.

§ What I wear is pants. What I do is live. How I pray is breathe.

§ Tradition, which is always old, is at the same time ever new because it is always reviving—born again in each new generation, to be lived and applied in a new and particular way. Convention is simply the ossification of social customs.

§ The devil makes many disciples by preaching against sin. He convinces them that the great evil of sin, induces a crisis of  guilt by which “God is satisfied," and after that he lets them spend the rest of their lives meditating on the intense sinfulness and evident reprobation of other men.

guilt by which “God is satisfied," and after that he lets them spend the rest of their lives meditating on the intense sinfulness and evident reprobation of other men.

§ It is by desiring to grow in love that we receive the Holy Spirit, and the thirst for more charity is the effect of this more abundant reception.

§ The ever-changing reality in the midst of which we live should awaken us to the possibility of an uninterrupted dialogue with God. By this I do not mean continuous “talk,” or a frivolously conversational form of affective prayer which is sometimes cultivated in convents, but a dialogue of love and of choice. A dialogue of deep wills.

§ All who live only according to their five senses, and seek nothing beyond the gratification of their natural appetites for pleasure and reputation and power, cut themselves off from that charity which is the principle of all spiritual vitality and happiness because it alone saves us from the barren wilderness of our own abominable selfishness.

§ If we wait for some people to become agreeable or attractive before we begin to love them, we will never begin.

§ If you are too obsessed with success, you will forget to live. If you have learned only how to be a success, your life has probably been wasted.

§ [I]t is of the very essence of Christianity to face suffering and death not because they are good, not because they have meaning, but because the resurrection of Jesus has robbed them of their meaning.

§ Whether you understand it or not, God loves you, is present in you, lives in you, dwells in you, calls you, saves you and offers you an understanding and compassion which are like nothing you have ever found in a book or heard in a sermon.

§ It is useless to try to make peace with ourselves by being pleased with everything we have done. In order to settle down in the quiet of our own being we must learn to be detached from the results of our own activity.

§ Hell was where no one has anything in common with anyone else except the fact that they all hate one other and cannot get away from each other and from themselves.

§ As long as we are on earth, the love that unites us will bring us suffering by our very contact with one another, because this love is the resetting of a Body of broken bones. Even saints cannot live with saints on this earth without some anguish, without some pain at the differences that come between them.

§ There is an absolute need for the solitary, bare, dark, beyond-concept, beyond-feeling type of prayer. Not of course for everybody. But unless that dimension is there in the Church somewhere, the whole caboodle lacks life and light and intelligence.

§ Writing about Boris Pasternak, Russian poet and novelist, after he refused the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1958: On the whole our reaction was to admire Pasternak with fervent accolades: to admire him in the courage and integrity we lack in ourselves.  Perhaps we can taste a little vicarious revolutionary joy without doing anything to change our own lives. To justify our own condition of servility and spiritual prostitution we think it sufficient to admire another man's integrity.

Perhaps we can taste a little vicarious revolutionary joy without doing anything to change our own lives. To justify our own condition of servility and spiritual prostitution we think it sufficient to admire another man's integrity.

Cold War addendum: In 2014 declassified documents reveal the US Central Intelligence Agency mounted a massive campaign in support of Pasternak’s nomination for the Nobel Prize, including buying and distributing thousands of copies of his novel, Doctor Zhivago.

§ [T]he conception of “separation from the world” that we have in the monastery too easily presents itself as a complete illusion: the illusion that by making vows we become a different species of being, pseudo-angels, “spiritual beings,” people of interior life, what have you.

§ If I affirm myself as a Catholic merely by denying all that is Muslim, Jewish, Protestant, Hindu, Buddhist, etc., in the end I will find that there is not much left for me to affirm as a Catholic: and certainly no breath of the Spirit with which to affirm it.

§ The last thing the salesperson wants is for the buyer to become content. You are of no use in our affluent society unless you are always just about to grasp what you never have.

§ When the angel spoke, God awoke in the heart of this girl of Nazareth and moved within her like a giant. He stirred and opened His eyes and her soul and she saw that, in containing Him, she contained the world besides. The Annunciation was not so much a vision as an earthquake in which God moved the universe and unsettled the spheres.

§ We live in a society whose whole policy is to excite every nerve in the human body and keep it at the highest pitch of  artificial tension, to strain every human desire to the limit and to create as many new desires and synthetic passions as possible, in order to cater to them with the products of our factories and printing presses and movie studios and all the rest.

artificial tension, to strain every human desire to the limit and to create as many new desires and synthetic passions as possible, in order to cater to them with the products of our factories and printing presses and movie studios and all the rest.

§ Buddhism refuses to countenance any self-cultivation or beautification of the soul. It ruthlessly exposes any desire of enlightenment or of salvation that seeks merely the glorification of the ego and the satisfaction of its desires in a transcendent realm. It is not that this is “wrong” or “immoral” but that it is simply impossible.

§ The truth of the matter is that you can hardly set Christianity and Zen side by side and compare them. This would almost be like trying to compare mathematics and tennis. And if you are writing a book on tennis which might conceivably be read by mathematicians, there is little point in bringing mathematics into the discussion.

§ They [referring to participants in a walk from San Francisco to Moscow plagued with many difficulties] are all concerned about the fact that their own human failings and incompatibilities came out a bit. That is all right, though. It has to be that way. Another form of poverty that we have to accept. We have got to be instruments of God and realize at the same time that we are very poor and defective instruments. It is important to resist the feelings of resentment and impatience we get over our own failings because this makes us project our faults onto other people, instead of bearing their burdens along with our own.

§ Vocation does not come from a voice out there calling me to be something I am not. It comes from a voice in here calling me to be the person I was born to be.

§ Despair is the absolute extreme of self-love. It is reached when we deliberately turn our back on all help from anyone else in order to taste the rotten luxury of knowing ourselves to be lost . . . Despair is the ultimate development of a pride so great and so stiff-necked that it selects the absolute misery of damnation rather than accept happiness from the hands of God. . . . But those who are truly humble cannot despair, because in a humble person there is no longer any such thing as self-pity.

§ As long as we secretly adore ourselves, our own deficiencies will remain to torture us with an apparent defilement. But if we live for others, we will gradually discover that no one expects us to be “as gods.”

§ To say that I am made in the image of God is to say that love is the reason for my existence, for God is love. Love is my true identity. Selflessness is my true self. Love is my true character. Love is my name.

§ Peace demands . . . greater heroism than war.

§ Only those who have had to face despair are really convinced that they needs mercy. Those who do not want mercy never  seek it. It is better to find God on the threshold of despair than to risk our lives in a complacency that has never felt the need of forgiveness.

seek it. It is better to find God on the threshold of despair than to risk our lives in a complacency that has never felt the need of forgiveness.

§ If in loving [others] we do not love what they are, but only their potential likeness to ourselves, then we do not love them: we only love the reflection of ourselves we find in them

§ All forms of taking pride in ourselves have a dangerous potential in the spiritual life. If I make anything out of the fact that I am Thomas Merton, I am dead. And if you make anything out of the fact that you are in charge of the pig barn (a dubious distinction which I had recently received and which I considered to involve some kind of promotion in status) you are dead. The moment you make anything out of anything you are dead.

§ Art enables us to find ourselves and lose ourselves at the same time.

§ War represents a vice that humankind would like to get rid of but which it cannot do without. We are like alcoholics who knows that drink will destroy them but who always have a reason for drinking. So with war.

§ We can no longer afford to equate faith with the acceptance of myths about our nation . . . [or] to equate hope with a naïve confidence in our image of ourselves as the good guys against whom all the villains in the world are leagued in conspiracy.

§ [In World War II] God was drafted into all the armies and invited to get out there and kill Himself.

§ We are in fact an adolescent society—a society that likes to play “chicken” not with fast cars, but with ballistic missiles.

§ Christmas, then, is not just a sweet regression to breast-feeding and infancy. It is a serious and sometimes difficult feast. Difficult especially if, for psychological reasons, we fail to grasp the indestructible kernel of hope that is in it. If we are just looking for a little consolation—we may be disappointed.

§ We must be willing to accept the bitter truth that, in the end, we may have to become a burden to those who love us. It takes heroic charity and humility to let others sustain us when we are absolutely incapable of sustaining ourselves.

§ Everybody makes fun of virtue, which by now has, as its primary meaning, an affectation of prudery practiced by hypocrites and the impotent.

§ Everybody makes fun of virtue, which by now has, as its primary meaning, an affectation of prudery practiced by hypocrites and the impotent.

§ Contemplation cannot be taught. It cannot even be clearly explained. It can only be hinted at, suggested, pointed to, symbolized. The more objectively and scientifically you try to analyze it, the more you empty it of its real content, for this experience is beyond the reach of verbalization and of rationalization.

§ We too often forget that faith is a matter of questioning and struggle before it becomes one of certitude and peace. You have to doubt and reject everything else in order to believe firmly in Christ, and after you have begun to believe, your faith itself must be tested and purified. Christianity is not merely a set of forgone conclusions. Faith tends to be defeated by the burning presence of God in mystery, and seeks refuge from God, flying to comfortable social forms and safe convictions in which purification is no longer an inner battle but a matter of outward gesture.

§ The bad writing I have done has all been authoritarian, the declaration of musts and the announcement of punishments.

§ I have learned that an age in which politicians talk about peace is an age in which everybody expects war: the world’s leaders would not talk of peace so much if they did not secretly believe it possible, with one more war, to annihilate their enemies forever. Always, "after just one more war" it will dawn, the new era of love: but first everybody who is hated must be eliminated. For hate, you see, is the genesis of their kind of love.

§ Is faith a narcotic dream in a world of heavily-armed robbers, or is it an awakening? Is faith a convenient nightmare in which we are attacked and obliged to destroy our attackers? What if we awaken to discover that we are the robbers, and our destruction comes from the root of hate in ourselves?

§ Suppose that my "poverty" be a hunger for spiritual riches: suppose that by pretending to empty myself, pretending to be silent, I am really trying to cajole God into enriching me with some experience—what then? . . . If my prayer . . . seeks only an enrichment of my own self, my prayer will be my greatest potential distraction.

§ Christ is born to us today, in order that He may appear to the whole world through us.

§ One of the most important things to do is to keep cutting deliberately through political lines and barriers and emphasizing the fact that these are largely fabrications and that there is another dimension, a genuine reality, totally opposed to the fictions of politics: the human dimension which politicians pretend to arrogate entirely to themselves.

§ One of the most important things to do is to keep cutting deliberately through political lines and barriers and emphasizing the fact that these are largely fabrications and that there is another dimension, a genuine reality, totally opposed to the fictions of politics: the human dimension which politicians pretend to arrogate entirely to themselves.

§ It is not sufficient to forgive others: we must forgive them with humility and compassion. If we forgive them without humility, our forgiveness is a mockery: it presupposes that we are better than they.

§ If you want to know what is meant by "God's will", this is one way to get a good idea of it. "God's will" is certainly found in anything that is required of us in order that we may be united with one another in love.

§ Prayer and love are really learned in the hour when prayer becomes impossible and your heart turns to stone.

§ To hope is to risk frustration. Therefore, make up your mind to risk frustration.

§ If you want to identify me, ask me not where I live, or what I like to eat, or how I comb my hair, but ask me what I think I am living for, in detail, and ask me what I think is keeping me from living fully for the thing I want to live for. Between these two answers you can determine the identity of any person.

§ Let me say this before rain becomes a utility that they can plan and distribute for money. By "they" I mean the people who cannot understand that rain is a festival, who do not appreciate its gratuity, who think that what has no price has no value, that what cannot be sold is not real, so that the only way to make something actual is to place it on the market. The time will come when they will sell you even your rain. At the moment it is still free, and I am in it. I celebrate its gratuity. . . . I listen [to the rain], because it reminds me again and again that the whole world runs by rhythms I have not yet learned to recognize, rhythms that are not those of the engineer. . . . As long as it talks I am going to listen.

§ A Brother asked one of the elders: What good thing shall I do and have life thereby? The old man replied: God alone knows what is good. However, I have heard it is said that someone inquired of Father Abbot Nisteros the great, the friend of Abbot Anthony, asking: What good work shall I do? and that he replied: Not all works are alike. For Scripture says that Abraham was hospitable and God was with him. Elias loved solitary prayer, and God was with him. And David was humble, and God was with him. Therefore, whatever you see your soul to desire according to God. Do that thing, and you shall keep your heart safe.

# # #

Ken Sehested @ prayerandpolitiks.org

"God acted . . . as a father who has two daughters: one very white, full of grace and gentility; the other very ugly, bleary-eyed, stupid and bestial. If the first is to be married, she doesn't need a dowry, but only to be put in the palace and those who want to marry her would compete for her. For the ugly, stupid, foolish wretch, it isn't enough to give her a large dowry, many jewels, lovely magnificent, and expensive clothes. . . .

"God acted . . . as a father who has two daughters: one very white, full of grace and gentility; the other very ugly, bleary-eyed, stupid and bestial. If the first is to be married, she doesn't need a dowry, but only to be put in the palace and those who want to marry her would compete for her. For the ugly, stupid, foolish wretch, it isn't enough to give her a large dowry, many jewels, lovely magnificent, and expensive clothes. . . .

Born in 1484, Las Casas first traveled to the island of Hispaniola in 1502 along with his father, a Spanish merchant. Initially he participated in and profited from Spain’s enslavement of the population. In 1510 he was the first priest to be ordained in the Americas.

Born in 1484, Las Casas first traveled to the island of Hispaniola in 1502 along with his father, a Spanish merchant. Initially he participated in and profited from Spain’s enslavement of the population. In 1510 he was the first priest to be ordained in the Americas. “They made some low wide gallows on which the hanged victims, feet almost touching the ground, stringing up their victims in lots of thirteen, in memory of Our Redeemer and His twelve Apostles, then set burning wood at their feet and thus burned them alive.

“They made some low wide gallows on which the hanged victims, feet almost touching the ground, stringing up their victims in lots of thirteen, in memory of Our Redeemer and His twelve Apostles, then set burning wood at their feet and thus burned them alive. blind sightedness. Not your stereotypical candidates for sainthood. In other words, folk like us, like the ones in our churches and neighborhoods and families.

blind sightedness. Not your stereotypical candidates for sainthood. In other words, folk like us, like the ones in our churches and neighborhoods and families. session of Congress, lifted Merton's name for special recognition (along with three other Americans), it seemed timely to move up the schedule. (Continue reading Ken Sehested’s "

session of Congress, lifted Merton's name for special recognition (along with three other Americans), it seemed timely to move up the schedule. (Continue reading Ken Sehested’s " § The humble receive praise the way a clean window takes the light of the sun. The truer and more intense the light is, the less you see of the glass. . . . Humility is the surest sign of strength.

§ The humble receive praise the way a clean window takes the light of the sun. The truer and more intense the light is, the less you see of the glass. . . . Humility is the surest sign of strength. § Few Christians have been able to face the fact that non-violence comes very close to the heart of the Gospel ethic, and is perhaps essential to it. But non-violence is not simply a matter of marching with signs under the eyes of unfriendly police. The partial failure of liberal non-violence has brought out the start reality that our society itself is radically violence and that violence is built into its very structure.

§ Few Christians have been able to face the fact that non-violence comes very close to the heart of the Gospel ethic, and is perhaps essential to it. But non-violence is not simply a matter of marching with signs under the eyes of unfriendly police. The partial failure of liberal non-violence has brought out the start reality that our society itself is radically violence and that violence is built into its very structure. frenzy of the activist neutralizes his work for peace. It destroys the fruitfulness of his own work, because it kills the root of inner wisdom which makes work fruitful.

frenzy of the activist neutralizes his work for peace. It destroys the fruitfulness of his own work, because it kills the root of inner wisdom which makes work fruitful. § Your life is shaped by the end you live for. You are made in the image of what you desire.

§ Your life is shaped by the end you live for. You are made in the image of what you desire. § Be still: / There is no longer any need of comment. / It was a lucky wind / That blew away his halo with his cares, / A lucky sea that drowned his reputation.

§ Be still: / There is no longer any need of comment. / It was a lucky wind / That blew away his halo with his cares, / A lucky sea that drowned his reputation.

§ A white detective in Birmingham, watching the children file by the score into paddy wagons, gave expression to the mind of the nation when he said: “If this is religion, I don’t want any part of it.” If this is really what the mind of white America has concluded, we stand judged by our own thought.

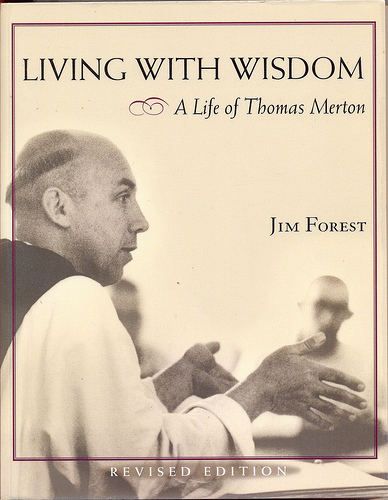

§ A white detective in Birmingham, watching the children file by the score into paddy wagons, gave expression to the mind of the nation when he said: “If this is religion, I don’t want any part of it.” If this is really what the mind of white America has concluded, we stand judged by our own thought. There are more than two dozen Merton biographies. Of the ones I’ve read, Jim Forest’s Living With Wisdom: A Life of Thomas Merton (revised edition, 2008) is far and away the best. (While you’re at it, Forest’s biography of Dorothy Day, All Is Grace, is also my favorite in that collection.)

There are more than two dozen Merton biographies. Of the ones I’ve read, Jim Forest’s Living With Wisdom: A Life of Thomas Merton (revised edition, 2008) is far and away the best. (While you’re at it, Forest’s biography of Dorothy Day, All Is Grace, is also my favorite in that collection.) § It may be true that every prophet is a pain in the neck, but it is not true that every pain in the neck is a prophet. There is no more firmly entrenched expression of the false self than the self-proclaimed prophet.

§ It may be true that every prophet is a pain in the neck, but it is not true that every pain in the neck is a prophet. There is no more firmly entrenched expression of the false self than the self-proclaimed prophet. § The real freedom is the freedom to be able to come and go from that center (essence of you, spark of the soul), and to be able to do without anything that is not immediately connected to that center. Because when we die, everything is destroyed except this one thing, which is our reality and which is the reality that God preserves forever.

§ The real freedom is the freedom to be able to come and go from that center (essence of you, spark of the soul), and to be able to do without anything that is not immediately connected to that center. Because when we die, everything is destroyed except this one thing, which is our reality and which is the reality that God preserves forever. § I am sick up to the teeth and beyond the teeth, up to the eyes and beyond the eyes, with all forms of projects and expectations and statements and programs and explanations of anything, especially explanations about where we are all going, because where we are all going is where we went a long time ago, over the falls. We are in a new river and we don’t know it.

§ I am sick up to the teeth and beyond the teeth, up to the eyes and beyond the eyes, with all forms of projects and expectations and statements and programs and explanations of anything, especially explanations about where we are all going, because where we are all going is where we went a long time ago, over the falls. We are in a new river and we don’t know it. declaration, then ascends quietly into the silence of Heaven which resounds with unending praise.

declaration, then ascends quietly into the silence of Heaven which resounds with unending praise. § It is the love of my lover, my neighbor or my child that sees God in me, makes God credible to myself in me. And it is my love for my lover, my child, my neighbor, that enables me to show God to each.

§ It is the love of my lover, my neighbor or my child that sees God in me, makes God credible to myself in me. And it is my love for my lover, my child, my neighbor, that enables me to show God to each. alone the power to make war while all other countries would be unable to do so. . . . War is therefore made in order to keep or to increase the means of making war. All international politics revolve in this vicious circle.

alone the power to make war while all other countries would be unable to do so. . . . War is therefore made in order to keep or to increase the means of making war. All international politics revolve in this vicious circle. § Prayers and sacrifice must be used as the most effective spiritual weapons in the war against war, and like all weapons they must be used with deliberate aim: not just with a vague aspiration for peace and security, but against violence and against war. This implies that we are also willing to sacrifice and restrain our own instinct for violence and aggressiveness in our relations with other people. We may never succeed in this campaign, but whether we succeed or not, the duty is evident. It is the great Christian task of our time. Everything else is secondary, for the survival of the human race itself depends upon it.

§ Prayers and sacrifice must be used as the most effective spiritual weapons in the war against war, and like all weapons they must be used with deliberate aim: not just with a vague aspiration for peace and security, but against violence and against war. This implies that we are also willing to sacrifice and restrain our own instinct for violence and aggressiveness in our relations with other people. We may never succeed in this campaign, but whether we succeed or not, the duty is evident. It is the great Christian task of our time. Everything else is secondary, for the survival of the human race itself depends upon it. more concrete it is, the better. One is not worried about the results of what is done. One is content to have good motives and not too anxious about making mistakes. In this way one can swim with the living stream of life and remain at every moment in contact with God, in the hiddenness and ordinariness of the present moment with its obvious task.

more concrete it is, the better. One is not worried about the results of what is done. One is content to have good motives and not too anxious about making mistakes. In this way one can swim with the living stream of life and remain at every moment in contact with God, in the hiddenness and ordinariness of the present moment with its obvious task. What are we to do? The duty of Christians in this crisis is to strive with all our power and intelligence, with our faith, hope in Christ, and love for God and humankind, to do the one task which God has imposed upon us in the world today. That task is to work for total abolition of war.

What are we to do? The duty of Christians in this crisis is to strive with all our power and intelligence, with our faith, hope in Christ, and love for God and humankind, to do the one task which God has imposed upon us in the world today. That task is to work for total abolition of war. self-righteousness, and refrain from being satisfied with dramatic, self-justifying gestures. . . . Christian nonviolence . . . is convinced that the manner in which the conflict for truth is waged will itself manifest or obscure the truth.

self-righteousness, and refrain from being satisfied with dramatic, self-justifying gestures. . . . Christian nonviolence . . . is convinced that the manner in which the conflict for truth is waged will itself manifest or obscure the truth.

the center of the shopping district, I was suddenly overwhelmed with the realization that I loved all these people, that they were mine and I theirs, that we could not be alien to one another even though we were total strangers. It was like waking from a dream of separateness, of spurious self-isolation in a special world.

the center of the shopping district, I was suddenly overwhelmed with the realization that I loved all these people, that they were mine and I theirs, that we could not be alien to one another even though we were total strangers. It was like waking from a dream of separateness, of spurious self-isolation in a special world. guilt by which “God is satisfied," and after that he lets them spend the rest of their lives meditating on the intense sinfulness and evident reprobation of other men.

guilt by which “God is satisfied," and after that he lets them spend the rest of their lives meditating on the intense sinfulness and evident reprobation of other men. Perhaps we can taste a little vicarious revolutionary joy without doing anything to change our own lives. To justify our own condition of servility and spiritual prostitution we think it sufficient to admire another man's integrity.

Perhaps we can taste a little vicarious revolutionary joy without doing anything to change our own lives. To justify our own condition of servility and spiritual prostitution we think it sufficient to admire another man's integrity. artificial tension, to strain every human desire to the limit and to create as many new desires and synthetic passions as possible, in order to cater to them with the products of our factories and printing presses and movie studios and all the rest.

artificial tension, to strain every human desire to the limit and to create as many new desires and synthetic passions as possible, in order to cater to them with the products of our factories and printing presses and movie studios and all the rest. seek it. It is better to find God on the threshold of despair than to risk our lives in a complacency that has never felt the need of forgiveness.

seek it. It is better to find God on the threshold of despair than to risk our lives in a complacency that has never felt the need of forgiveness. § Everybody makes fun of virtue, which by now has, as its primary meaning, an affectation of prudery practiced by hypocrites and the impotent.

§ Everybody makes fun of virtue, which by now has, as its primary meaning, an affectation of prudery practiced by hypocrites and the impotent. § One of the most important things to do is to keep cutting deliberately through political lines and barriers and emphasizing the fact that these are largely fabrications and that there is another dimension, a genuine reality, totally opposed to the fictions of politics: the human dimension which politicians pretend to arrogate entirely to themselves.

§ One of the most important things to do is to keep cutting deliberately through political lines and barriers and emphasizing the fact that these are largely fabrications and that there is another dimension, a genuine reality, totally opposed to the fictions of politics: the human dimension which politicians pretend to arrogate entirely to themselves.

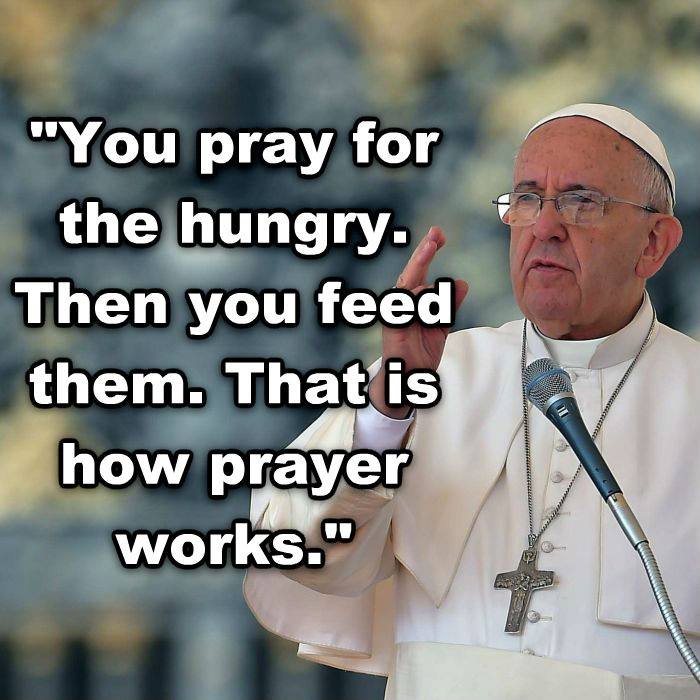

Pope Francis’ choice to publicly name Merton along with Dorothy Day, Martin Luther King Jr., and Abraham Lincoln is stunning in a number of ways. Two were assassinated, one of them a Baptist pastor, the other who presided over the first contentious step in unraveling our nation’s brutal racial history. No surprise two others were Roman Catholics, but neither were ecclesial leaders. In fact, both gave fits to church hierarchies when they were alive.

Pope Francis’ choice to publicly name Merton along with Dorothy Day, Martin Luther King Jr., and Abraham Lincoln is stunning in a number of ways. Two were assassinated, one of them a Baptist pastor, the other who presided over the first contentious step in unraveling our nation’s brutal racial history. No surprise two others were Roman Catholics, but neither were ecclesial leaders. In fact, both gave fits to church hierarchies when they were alive. turned the United States Environmental Protection Agency’s approval of sulfoxaflor, a pesticide linked to the mass die-off of honeybees that pollinate a third of the world’s food supply.”

turned the United States Environmental Protection Agency’s approval of sulfoxaflor, a pesticide linked to the mass die-off of honeybees that pollinate a third of the world’s food supply.” ¶ Invocation. “Prayer is more than something I do. The longer I practice prayer, the more I think it is something that is always happening, like a radio wave that carries music through the air whether I tune in to it or not.” —Barbara Brown Taylor

¶ Invocation. “Prayer is more than something I do. The longer I practice prayer, the more I think it is something that is always happening, like a radio wave that carries music through the air whether I tune in to it or not.” —Barbara Brown Taylor ¶ Little Rock Nine anniversary. After weeks of resistance from Arkansas governor Orval Faubus, nine black students successfully enter Little Rock's Central High School on 25 September 1957 with protection from the National Guard and the 101st Airborne Division authorized by President Dwight D. Eisenhower.

¶ Little Rock Nine anniversary. After weeks of resistance from Arkansas governor Orval Faubus, nine black students successfully enter Little Rock's Central High School on 25 September 1957 with protection from the National Guard and the 101st Airborne Division authorized by President Dwight D. Eisenhower. ¶ Does your liturgy ever allow time for

¶ Does your liturgy ever allow time for  women with their arms stretched out to me over that line. But I can’t seem to get there no how. I can’t seem to get over that line.” —Viola Davis, first black woman to win the best actress in a drama category, in her award acceptance speech, quoting Harriet Tubman, the 19th century abolitionist who rescued dozens of slaves, then struggled for women’s voting rights after the Civil War. In her acceptance speech, Davis went on to say that “The only thing that separates women of color from anyone else is opportunity.”

women with their arms stretched out to me over that line. But I can’t seem to get there no how. I can’t seem to get over that line.” —Viola Davis, first black woman to win the best actress in a drama category, in her award acceptance speech, quoting Harriet Tubman, the 19th century abolitionist who rescued dozens of slaves, then struggled for women’s voting rights after the Civil War. In her acceptance speech, Davis went on to say that “The only thing that separates women of color from anyone else is opportunity.” ul, after buying the rights to a 62-year-old drug used for treating life-threatening parasitic infections and increasing the price overnight from $13.50 to $750. Several years ago, prior to being bought by different pharmaceutical companies several times, the drug cost $1.00 per tablet. —

ul, after buying the rights to a 62-year-old drug used for treating life-threatening parasitic infections and increasing the price overnight from $13.50 to $750. Several years ago, prior to being bought by different pharmaceutical companies several times, the drug cost $1.00 per tablet. — ¶ Last week’s prayer&politiks post featured “Days of awe and Meccan pilgrimage: Reflections on the confluence of Jewish and Islamic holy days.” Here’s another reflection—“

¶ Last week’s prayer&politiks post featured “Days of awe and Meccan pilgrimage: Reflections on the confluence of Jewish and Islamic holy days.” Here’s another reflection—“