by Ken Sehested

Context: On 8 February 2003 Rev. Ken Sehested traveled to Iraq for three weeks as a member of the Iraq Peace Team, a project of Voices in the Wilderness, calling for an end to the threat of war by the U.S.

Prior to going, the Asheville (N.C.) Citizen-Times newspaper published his article, “Journey to Iraq,” as a guest editorial and asked Sehested to write three weekly columns for the newspaper while in Iraq. Printed below is the initial article followed by three columns posted from Baghdad. The latter are titled “Caitlin Letters,” written as open letters to Caitlin Wood, a member of Circle of Mercy Congregation in Asheville. Caitlin was among the more than 200 high school students in Asheville who participated in the 6 March 2003 “Books Not Bombs” nationwide school walk-out in opposition to war on Iraq.

Sehested previously traveled to Iraq in March 2000 as part of an interfaith delegation of Jews, Christians and Muslims from the U.S.

Journey to Iraq: Of risk and reverence

I leave for Iraq February 8, on a three-week enlistment with the Iraq Peace Team. Seven of us will go in this weekend, to join a contingent of approximately 25 others currently in Baghdad, most from the U.S., some from Canada and the U.K. The majority stay for a month, sometimes more.

I go under the banner of Voices in the Wilderness, sponsors of the Peace Team. While there we will see and experience as much of reality on the ground as is possible in a short time. We’ll visit schools, hospitals, international humanitarian aid headquarters and cultural centers; have conversations with Islamic and Christian and government and neighborhood leaders. I hope to see again the traditional site of Abraham’s birthplace in the southern part of the country; view the confluence of the Tigris and Euphrates Rivers; talk with Kurdish leaders in the north.

What I don’t look forward to is the omnipresent billboards with Saddam Hussein’s picture. For that matter, neither do I relish listening again to the stories of mothers whose babies are dying from something as simple as diarrhea or as menacing as leukemia. Both ailments, among a host of others, are epidemic in scale in Iraq. And Saddam Hussein, brutal as he is, did not cause these. Tens of thousands of tons of depleted uranium—cancer-causing radioactive material—remain scattered across the landscape, leftover fragments applied to harden the casings of shells and bombs missiles fired by the U.S.-led coalition in the 1991 Gulf War.

Many of those weapons were also trained on the civilian infrastructure: water supply and sewage treatment and electrical grids—a flagrant violation of international law done with the full awareness (as declassified documents prove) by U.S. war planners that doing so would lead to exaggerated levels of child mortality. The U.N. sanctions have severely hampered the reconstruction of these life-support systems. The water is Iraq is virtually poisonous, since importing chlorine is forbidden.

At least a million people—mostly the very young and the very old—have died since the end of the Gulf War for reasons directly related to the economic sanctions: a combination of impure water, poor nutrition and inadequate health care (in a country that before the Gulf War was the medical superpower of the Islamic world). These numbers come not from left-wing protestors or Iraqi propagandists but from the U.N.’s own agencies, backed up and supplemented by similar studies of other respected international aid agencies.

A million deaths seems like the result of a weapon of mass destruction. Writing in 1999, foreign affairs scholars John Mueller and Karl Mueller wrote that the sanctions may have contributed to the deaths of more people ‘than have been slain by all so-called weapons of mass destruction throughout history.”

Communicating this reality—that the sanctions themselves, by far the longer economic embargo in human history—is what Voices in the Wilderness has devoted itself to since 1996. Kathy Kelly, a former Catholic parochial school teacher, just accompanied her 48th delegation of visitors to Iraq. Last year the organization was nominated for the Nobel Peace Prize.

I’m going back to Iraq this coming Saturday even though it is illegal for U.S. citizens to do so. The U.S. Treasury Department stipulates a maximum fine of $1,000,000 and 12 years in prison, plus a $250,000 administrative penalty.

My purpose is to cross, in a personal and public way, the wall of hostility between the citizens of Iraq and the U.S. And then, upon return, to report back what we have seen and heard, adding our voices to those calling for nonviolent alternatives to war and an end to the economic sanctions. I’ll add my voice to the others, including three ranking U.N. diplomats who have resigned their postings in Iraq in protest to the sheer inhumanity of the sanctions.

One of those three—Denis Halliday, former Assistant Secretary-General of the U.N. and humanitarian aid coordinator in Iraq—abandoned his lengthy diplomatic career to call attention to the fact that “we are destroying an entire society. It is as simple and terrifying as that.”

My decision to return to Iraq wasn’t made lightly. In the first place, I had to raise all my own travel expenses. Then there’s the threat of severe legal penalty. And also the chance the U.S. may implement its war plans while I’m there. A few folk have wondered aloud, in my presence, whether I’m crazy. Or suicidal. But my supporters are far more numerous. I’ve received the blessing of my wife, the commissioning of my local congregation (and of a local ecumenical prayer group), as well as the appointment as special envoy by the Alliance of Baptists. And I raised more money, quickly, than at any time in my life, including several donations from people I don’t even know who heard about my trip from others.

No doubt some will see this journey as treasonous, as “giving aid and comfort to the enemy.” I find it odd that a country as heavily churched as the U.S. can forget that among the imperatives of the New Testament is this one: “If your enemies are hungry, feed them” (Romans 12:20). Why is it that we are unfazed when well over a million U.S. military personnel are pledged to risk life and limb in service to their nation, yet think it outrageous when an occasional Christian does something similar for the Kingdom of God?

It is a risk, a calculated risk, to be sure. But the calculus of risk is always done in the context of reverence. All of us risk for the purposes and people we revere, we sacrifice for the values we hold dear. And I revere Jesus and his announced purpose. Indeed, I believe that loving enemies is the very heartbeat of the Gospel of Christ.

My journey is a statement of political dissent, even civil disobedience. But these are secondary matters. Before anything else, my journey is a spiritual discipline. Whenever I intentionally locate myself on the margins—in the places where life is battered, bruised and broken, in places far away or near at hand—I discover renewed clarity about the reality of God’s promise. And the invitation, inshallah, is extended again to be an accomplice in Heaven’s insurgency against the cycle of vengeance.

Such is the stuff of spiritual formation.

11 February 2003

Dear Caitlin

Monday morning. I made it to Jordan, just west of Iraq, and am about half-way to Baghdad. Not in distance, but in travel time. I spent about 12 hours in planes to this point. Tomorrow will take at least that much time to drive from Amman to Baghdad, 500 miles, much of it through some of the most barren desert anywhere.

We arrived last night to the Al Monzer Hotel, Amman, Jordan, and this morning I’ve got the jet-lagged jitters. The sun is just about to rise, and the rays of new light are in a fierce argument with the back of my eyelids on what time it really is. I’m hoping a cup of coffee will bring a truce.

As the water boiled in the help-yourself kitchen just off the hotel lobby, I happened to notice a week-old copy of the English-language Jordan Times, turned to the page with the horoscope column. I got a chuckle when reading mine: “Can you find a way to get out for a change of scenery? It would do you a world of good. Make it someplace really special.” My change of scenery, from Brevard Road to Baghdad, probably wasn’t what the planetary diviner had in mind. But as far as the earth goes, few locations are as dependent on life and death choices to be made in the coming weeks. So, yes, I think it’s special.

Wednesday morning. We made it Baghdad, safe and sound, though things got a little tense at the Iraqi border. For a while I thought I’d have to hitch-hike back to Amman, alone. In the rush to get ready, I completely forgot until it was too late that I have an Israeli visa stamped in my passport, from my spring trip to the Occupied West Bank of Palestine. And the Iraqis won’t let you in if you have that. (Remind me to tell you that story when I get home!)

I’ve already told you about Voices in the Wilderness, which sponsors the Iraq Peace Team. But there’s also a delegation from Christian Peacemaker Teams, an ecumenical group founded by Mennonites, Brethen and Quakers who train Christians and locate them in various war-torn regions of the world as advocates of nonviolent alternatives to conflict. (It’s probably the most organized and effective response I know to fulfill Jesus’ demand to love enemies.)

The two groups work hand-in-hand here. Last night, right after arriving, the entire group met in one big circle. I counted 43, most from the U.S. but with a strong Canadian contingency as well as others from The Netherlands, Ireland, Scotland and Australia. Nearly half this group is committed to staying indefinitely—“until peace breaks out,” as one said last night, or at least until the war is called off. The rest of us are here anywhere between 10 days to a month.

The group is loosely but effectively organized into various task-units, everything from media work to action strategies (in and around Baghdad and beyond) to visits for conversation with Iraqi citizens in places like hospitals, cultural centers, mosques and churches. (Most in the U.S. don’t realize there are nearly one million Christians here in Iraq, including some of the oldest congregations. In the sixth century Christian missionaries from this land were traveling to India and China.)

But then, most of us know almost nothing about Iraq. And that’s partly on purpose, I believe, since it’s always harder to kill someone you know, someone who doesn’t have a name or a history or even a face but is just a target, is expendable, however remorsefully and regretfully, in the cause of “justice” and for the sake of “peace.” You remember the name of Timothy McVeigh, the homegrown terrorist who was executed for bombing the federal building in Oklahoma City and who confessed that he almost didn’t go through with it when he learned there was a daycare center in the building. But he decided that was unavoidable “collateral damage.” McVeigh was a veteran of the earlier war on Iraq, the Gulf War in 1991, and afterwards wrote in a letter to his aunt: “Killing Iraqis was hard at first, but after a while it got easier.” Or like current U.S. Secretary of State Colin Powell said when asked, in 1991, about the number of Iraqi casualties of that previous war: “That’s a number in which I have very little interest.”

I certainly didn’t know much until my first trip here three years ago. This region nestled between the Tigris and Euphrates Rivers (my hotel room looks out on the former) is thought to be the site of the first human civilization some 6,000 years ago. The wheel was probably invented here, as well as human writing. The earliest legal code explicitly based in what we would call “justice”—protecting the weak against the strong—was discovered here. The use of zero in mathematics, time measurement, hospitals and the formal study of architecture started here.

Abraham, spiritual heir to three-fourths of the world’s people (Jews, Christians and Muslims), was born here. The Magi, first visitors at Jesus’ birth, came from here, as did other biblical figures like Noah, Jonah, Ezekiel, Nehemiah and Daniel—not to mention ol’ King Nebuchadnezzar.

My roommate’s just returned from an action in front of the United Nations compound here in Baghdad, and he wants to go get some lunch. But he said that, for the first time, a staff member in that building came and told our vigiling members that our presence there was a boost for their morale! What a delightful way to begin what could be an eventful stay.

More later. Tell your folks I say “hey.”

17 February 2003

Dear Caitlin

This trip is a little riskier than others I’ve taken to conflicted regions. And, yes, I’ve had moments of wondering if I fully knew what I’m getting into.

The Iraq Peace Team is split between three hotels in Baghdad—beautiful hotels, once upon a time, but a bit sad now. When I first got into my room, I noticed the windows each bore strips of clear plastic tape. At first I thought they were newly-installed and someone forgot to take off the tape. Then I realized (and later had it confirmed) that the tape was put there to retard glass shattering in case of bombing.

Then, yesterday, we got an official list of emergencies supplies to keep assembled in my small backpack in case we have to evacuate on short notice. It’s a sobering exercise, even more so for about half the group who are committed to staying indefinitely, war or no war. (The rest of us, including me, will attempt to leave if we get clear advance warning of an attack.)

So, why am I here? Is this crazy, or what?

I just stepped to my 5th floor window to watch a caravan of honking cars go by. Up front, in an old convertible, was a bride and groom sitting on the back of the back seat. A wedding party! Which is to say, life goes on here. You see soldiers occasionally, especially outside of hotels like ours during the evening hours, to make sure nothing happens to us.

This evening I took a walk to find some fresh fruit and found some at a street vendor about a mile away. Unfortunately, I didn’t have quite enough Iraqi dinari to pay him. He understood just enough English to realize what I was saying, and he asked, “Tomorrow?,” meaning, could I pay him the rest then? Given our schedule, I wasn’t sure I could get back tomorrow, so I tried to indicate that I would put back some of what I had selected.

As I tried to undo the knot in the plastic bag, he put his hand on mine, shaking his head, “No, no, no, is O.K.” Then he extended his hand, his left hand, to shake mine. His right hand was inconspicuously tucked in his coat pocket. Probably a war wound. Iraq was in a ten-year war with Iran in the ‘80s. They were a U.S. ally then. In fact, public records show that the U.S. government approved the sale to Iraq of all the components for the chemical weapons they used during that war.

And we offered no complaint after they did.

That’s the crazy thing about who’s a terrorist and who’s not. We usually refer to the latter as “freedom fighters.” Back when Afghanistan was aligned with the former Soviet Union—and when Moscow was declared by former President Reagan to be the center of a “global terror network”—our government poured tons of money into supporting Afghan “freedom fighters” at war with the Soviet army. Since then links have been made between those same people (including people like Osama bin Laden) and terrorist attacks in Algeria, Egypt, the 1993 World Trade Center bombing and the more recent suicide attack against the USS Cole.

Now a freedom fighter. Now a terrorist. It reminds me of the story about Alexander the Great, when he confronted a captured pirate ship captain. Alexander asked the man, “What is your idea, in infesting the sea?” To which the pirate asked back, “The same as yours, in infesting the earth! But because I do it with a tiny craft, I’m called a pirate. Because you do it with a mighty navy, you’re called an emperor.”

Back to my earlier question, about why I’m here. I’m here because (as one of my friends recently wrote) I believe that if Iraq’s economy, and that of its neighbors, were based on soy beans—instead of oil—we would not be threatening war.

I believe greed is the real reason for this conflict—a conflict between the leaders of two greedy nations, one large and powerful, one small and weak. I believe the Bible is exactly right when it says: Where do these conflicts come from? You want something and cannot have it, so you wage war (James 4:1-2).

I also believe that peace, like war, is waged. And that if you believe in something, really believe, you will be willing to take risks on its behalf.

Being here is risky. But it gives me a vantage point to see things more clearly. And what I see I’m able to communicate to people like you who have the hard job of convincing people there that war is not the answer to this conflict—in fact, that war will make things much, much worse.

Tomorrow I’m going to find that street vendor and pay him the rest of the money I owe.

25 February 2003

Dear Caitlin

I returned this evening from the infamous border between Iraq and Kuwait, marked by a 25-foot high wall of sand stretching as far as the eye could see. Our Iraq Peace Team set up an encampment in the demilitarized zone which separates the two countries, about 50 yards from the U.N.-monitored checkpoint. Bangladesh currently supplies the soldiers serving under the U.N. flag at this flashpoint. They waived at us several times during the day, and officers from France and Russia came out to chat at different times.

Somewhere beyond that horizon half of the 180,000 U.S. troops now ringing Iraq will come pouring in. They will cross the very place where we prayed and sang, displayed banners and enlarged photos of ordinary Iraqi citizens who will bear the blood payment for this showdown between a dictatorial regime and an empire addicted to oil.

If it comes, it will not be a battle. It will be a slaughter. As one ancient historian, documenting the earlier, Roman empire, wrote: “They create desolation and call it peace.”

Our group began a four-day, water-only fast following our Sunday evening news conference at the press center in Baghdad, where we released a statement to a gaggle of journalists and camera crews explaining this border initiative. The statement notes that “decisions [made by the U.S.] in the next few weeks will forever change the lives of millions of people.” It calls on people everywhere, but especially in the U.S., to conduct a massive, preemptive sit-down for peace, saying “Peace can still be preserved. Devastation can still be avoided. But you must go beyond what you think you can do. You must up the ante. With cataclysm hanging over our heads you must refuse to conduct business as usual.”

The writer of Proverbs said: “Where there is no vision, the people perish” (29:17). Sometimes, to see the center clearly, you have to go to the boundary; because what you see depends on where you stand.

The southern-most area of Iraq, to where we traveled Monday morning, is a most unusual bioregion. I don’t know if there is such a thing as a “desert marshland,” but this is what my untrained eye sees: minimal vegetation yet high humidity and an even higher water table, with frequent plots of standing water. Eons ago the confluence of the Tigris and Euphrates Rivers (among other smaller rivers) created a massive marshland emptying into the Persian Gulf. The area birthed a distinctive culture, now virtually extinct, sometimes referred to as “the Venice of the Middle East.”

This area where we encamped, about an hour’s drive southwest of Basra, is now toxic. Cancer rates are five times higher than before the ’91 Gulf War. No doubt there are multiple causes. But the leading suspect is the 300 tons of depleted uranium deposited here during “Operation Desert Storm,” in the form of armor-piercing coatings on munitions fired by the U.S.-led coalition forces expelling the Iraqi military from Kuwait. Tuck away this story in your mind, Caitlin. I am convinced that by the time you reach adulthood the documented story of this form of biological warfare will finally be exposed.

During my brief borderline vigil several questions formed in my mind, in response to the Bush Administration’s fervent insistence—always coated in references to moral virtue—that justice in Iraq can only be bargained with the barrel of a gun.

•If war is justified, why have most Christian denominations in the U.S., and many in other nations, spoken publicly against such a war? (This includes President Bush’s own pastor.)

•If war is justified, why do all of Iraq’s neighbors oppose war at least without explicit U.N. approval. (Turkey, a traditional ally in the region, asked for twice the $18,000,000,000 U.S. offer for troop deployment along their border with Iraq. How is this different from bribery?)

•If war is justified, why do most U.S. allies, the vast majority of the family of nations and a simple majority of U.S. citizens also object to unilateral action? And if war is launched anyway, will our democratic political tradition also be a casualty?

•In World War I, it is estimated that 80% of the casualties were soldiers; in World War II, that number had dropped to 50 percent. Given the technology of modern warfare, the percentage of civilian casualties is up to 90%, and for every combatant fatality seven children die. Can any war be just? (Or is it JUST war?)

I, for one, believe such moral appeals (like depleted uranium-tipped shells) are designed to pierce the consciences of people here and everywhere who share an elementary commitment to justice, fairness and truth-telling.

I, for one, believe that such a war will merely scatter the germinating seeds of future wars.

I, for one, believe that we as a people are caught in a history we do not understand and could very well suffer the consequence of all who forfeit vision, who barter justice for security.

Think about these questions, and make your own list. We’ll talk when I get home in a few days. For now, the muezzin is just now issuing the call to prayer from the nearby mosque. Jews, Christians and Muslims agree that the call to prayer is a call to spiritual vision; but also that such spirituality transforms political vision as well: “Thy kingdom come, on earth. . . .” (Matthew 6:10).

Hope to see you soon!

###

shall displace / All sorrow by thy grace, mercy bound, mercy bound / All sorrow by thy grace, circle ‘round. —new verse to “

shall displace / All sorrow by thy grace, mercy bound, mercy bound / All sorrow by thy grace, circle ‘round. —new verse to “ ¶ Remembering Marcus Borg. “It’s so easy to feel overwhelmed when we see injustice, greed and a broken world with so many needs. Sometimes it’s just too much and we become paralyzed. . . . Asked how to avoid becoming overwhelmed, theologian Marcus Borg said, ‘It’s like being part of a quilter’s group. Don’t worry about the entire quilt; just focus on your square.’” —Tom Peterson,

¶ Remembering Marcus Borg. “It’s so easy to feel overwhelmed when we see injustice, greed and a broken world with so many needs. Sometimes it’s just too much and we become paralyzed. . . . Asked how to avoid becoming overwhelmed, theologian Marcus Borg said, ‘It’s like being part of a quilter’s group. Don’t worry about the entire quilt; just focus on your square.’” —Tom Peterson,  act. Most people realize that the KKK doesn’t represent Christian teachings. That’s what I and other Muslims long for—the day when these terrorists praising Muhammad or Allah’s name as they debase their actual teachings are instantly recognized as thugs disguising themselves as Muslims.” —Kareem Abdul-Jabbar, former National Basketball Association Most Valuable Player, now a New York Times best-selling author and filmmaker, in Time magazine

act. Most people realize that the KKK doesn’t represent Christian teachings. That’s what I and other Muslims long for—the day when these terrorists praising Muhammad or Allah’s name as they debase their actual teachings are instantly recognized as thugs disguising themselves as Muslims.” —Kareem Abdul-Jabbar, former National Basketball Association Most Valuable Player, now a New York Times best-selling author and filmmaker, in Time magazine “Without a face, the self can form only with the rejections of all otherness, with a generalized, all-purpose contempt. . . . A world stripped, not merely of ethics, but of the biological and cultural foundation of ethics.”

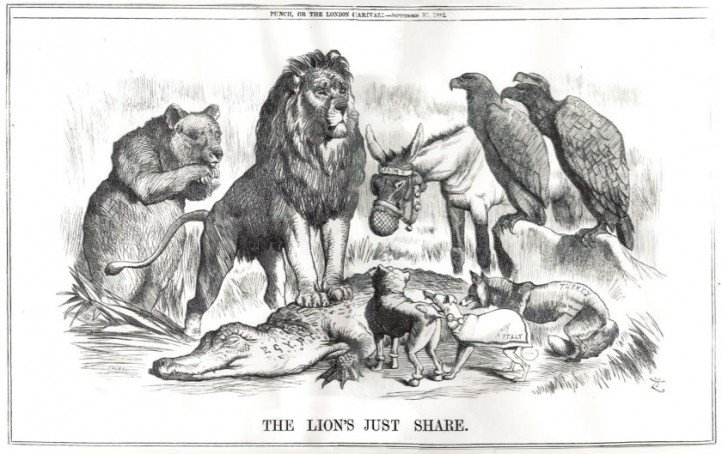

“Without a face, the self can form only with the rejections of all otherness, with a generalized, all-purpose contempt. . . . A world stripped, not merely of ethics, but of the biological and cultural foundation of ethics.” ¶ Sam Keen’s 1991 book, Faces of the Enemy: Reflections of the Hostile Imagination, is one of a number of books documenting how a nation’s war preparations require public relations efforts (a.k.a. propaganda) to rhetorically and visually depict the enemy as barbarian, even beastly, i.e., to remove the traces of actual faces and replace them with horrific characteristics.

¶ Sam Keen’s 1991 book, Faces of the Enemy: Reflections of the Hostile Imagination, is one of a number of books documenting how a nation’s war preparations require public relations efforts (a.k.a. propaganda) to rhetorically and visually depict the enemy as barbarian, even beastly, i.e., to remove the traces of actual faces and replace them with horrific characteristics.

¶ The first time ever I saw your face / I thought the sun rose in your eyes / And the moon and the stars were the gifts you gave / To the dark and the endless skies, my love / To the dark and the endless skies. —Ewan McCall song, made famous by Roberta Flack’s Grammy Award winning rendition in 1972. Haven’t heard it in a while? Here’s one of several

¶ The first time ever I saw your face / I thought the sun rose in your eyes / And the moon and the stars were the gifts you gave / To the dark and the endless skies, my love / To the dark and the endless skies. —Ewan McCall song, made famous by Roberta Flack’s Grammy Award winning rendition in 1972. Haven’t heard it in a while? Here’s one of several

¶

¶

¶ Mourning Kayla. “Some people find God in church. Some people find God in nature. Some people find God in love. I find God in suffering. I’ve known for some time what my life’s work is, using my hands as tools to relieve suffering.” —Kayla Mueller in a 2011 birthday card to her father. Mueller, a humanitarian aid worker from Arizona, was captured in August 2013 in Aleppo, Syria, by ISIS, which claimed this past week that Muller had been killed in an air strike. Mueller had worked with a variety of organizations, including an HIV/AIDS clinic and women’s shelter in Arizona, and aid work in India, Israel and Palestine. In December 2012 she began work with Syrian refugees in Turkey.

¶ Mourning Kayla. “Some people find God in church. Some people find God in nature. Some people find God in love. I find God in suffering. I’ve known for some time what my life’s work is, using my hands as tools to relieve suffering.” —Kayla Mueller in a 2011 birthday card to her father. Mueller, a humanitarian aid worker from Arizona, was captured in August 2013 in Aleppo, Syria, by ISIS, which claimed this past week that Muller had been killed in an air strike. Mueller had worked with a variety of organizations, including an HIV/AIDS clinic and women’s shelter in Arizona, and aid work in India, Israel and Palestine. In December 2012 she began work with Syrian refugees in Turkey. you’re looking for a good video resource (28 minutes) for Christian education on interfaith understanding, see this

you’re looking for a good video resource (28 minutes) for Christian education on interfaith understanding, see this  ¶ Toles cartoon. “You’re making exactly the same crazy impractical mistakes as Jesus.” —character in a Tom Toles

¶ Toles cartoon. “You’re making exactly the same crazy impractical mistakes as Jesus.” —character in a Tom Toles  a player on one of the NCAA football championship teams (8 January 2015). In other words, he plays with passion and a reckless, take-no-prisoners abandonment.

a player on one of the NCAA football championship teams (8 January 2015). In other words, he plays with passion and a reckless, take-no-prisoners abandonment.