“John’s act of writing a gospel, what he claims about Christ, and how he makes these claims, all represent fundamental rejection and subservience of Caesar’s power. . . . John believed that Christ is in every way superior to Caesar. . . . He reverses the normal public meaning of Jesus’ encounter with the agents of the Roman Empire” (p. ix).

Thatcher points out that the same story can have quite different meanings, e.g., a Jewish delegation meeting with Roman emperor, Caligula. One report, the official minutes of the encounter, shows the Jewish support of the emperor. Philo, a Jewish writer, points out what the Jewish delegation really felt. The story illustrates the two faces every victim of imperial power must always wear. “These things happened,” Philo says, “but they didn’t mean what the people in power thought they meant” (pp. 23-25). Thatcher develops his theory of public and “hidden transcripts,” “the little traditions,” the counter memories” (p. 26). “Every situation of conflict between Jesus and the authorities may be read at two levels: the normal public meaning of the events, and in John’s ‘little tradition,’ reinterpretation of those events as expressions of Christ’s absolute sovereignty” (p. 46).

In John’s story the Romans are not in control. The Jewish authorities, on whom Caesar depends, granting them the status of Roman prefects, are helpless, unable to stop Jesus’ mission or even protect their own interests (John 12, 18). Crucifixion was a major part of Roman policy of intimidation and control, but in John’s story fulfilled prophecy (e.g., division of Jesus’ clothing, Jesus’ death, the piercing with a spear) make the ultimate story of defeat end in conquest (p. 107). Jesus is in control to the very end. Even the Roman political order is not in final control. In John’s story, Pilate (the Roman governor) appears in seven scenes, without the results he wishes (28 verses; in the synoptics, Pilate gets a combined total of 37 verses), and the Roman governor “is afraid” (19:8). Even after his vicious scourging, Jesus continues his words coherently against Pilate (19:12). Rome’s victims followed Rome’s script; Jesus has his own script (even washing his disciples’ feet—a sharp retort to Roman imperial practise).

Read more ›

RIP: Guy Carawan

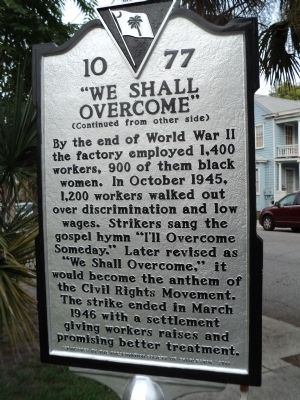

RIP: Guy Carawan Carawan, folk musician and musicologist who died this past week, is not well known outside certain musical and civil rights circles. A California native, he more than any other is responsible for what we now know as “We Shall Overcome.” (Here is an 8+ background

Carawan, folk musician and musicologist who died this past week, is not well known outside certain musical and civil rights circles. A California native, he more than any other is responsible for what we now know as “We Shall Overcome.” (Here is an 8+ background