by Ken Sehested

Circle of Mercy Congregation, first Sunday of Lent 2020

Text: Matthew 4:1-11

(The first draft was written late night of 25 February 2020, Shrove Tuesday, following the death of my Mom early that morning.)

“Isn’t there anything you understand?

It’s from the ash heap God is seen.

Always! Always from the ashes.”

—Archibald MacLeish in “J.B.,” a play based on the Book of Job

My Mama died today, in the wee hours before dawn. Nancy and I went and sat by her beside for a season of mourning and thanksgiving—in silence, though Mom’s favorite hymns were playing.

Some months ago Dale Roberts figured out how to implement what I wanted—which turned out to be a bluetooth device, with a built-in speaker, on whose memory chip he downloaded 10 hours of instrumental renditions of old hymns, the ones Mama knew well, playing in a repeating loop on a table near her weak ears.

The medical staff in the nursing facility where she lived—the past year in palliative care, mostly morphine—said  the music had a calming effect, just as I had hoped.

the music had a calming effect, just as I had hoped.

Right: Linocut art by Julie Lonneman.

When I hear traditional hymn music, it’s Mama’s voice I hear. My Dad couldn’t carry a tune in a bucket; and he knew it. Sometimes we would quietly hum—always off key. And sometimes he would mouth the words. So it’s Mama’s voice I hear in my head.

Without planning, Nancy and I ended our vigil as the closing bars of “Great Is Thy Faithfulness” played, followed by a prayer from Missy who joined us. Then I kissed Mama’s cold forehead and said my last goodbye.

Needless to say, my heart and mind and bones have roiled throughout the day, much of which was spent attending the multitude of details all surviving beloveds must do. By this evening, some clarity emerged.

There is a liturgical significance to the fact that Mama died on Shrove (from the root word for “absolve”) Tuesday, “Fat Tuesday,” Mardi Gras in southern US coastal towns, Carnival in countries like Brazil. You may have wondered why, in some Christian traditions, pancake suppers are held on Shrove Tuesday, the day before Ash Wednesday, inaugurating the Christian season of Lent.

By the Middle Ages, many in Christendom cooked pancakes to use up butter, eggs, and fat, before doing without those items during Lent. In Mardi Gras towns, the day is for extravagant partying, on the eve of the ashen season beginning the following day.

Mama would have enjoyed the fact that she died on Mardi Gras, which she knew about, since the second half of her life was lived down the bayous, southwest of New Orleans.

But Mama didn’t know what “liturgical” meant. She spent her life in deep-water, Southern-flavored, Baptist congregations, which didn’t acknowledge things like Lent and Advent. (And we downplayed Pentecost Sunday, since the Pentecostals made such a racket.)

Shrove Tuesday—“fat Tuesday” in Carnival’s lingo—is a day for fat-saturation and festivity. Followed by Ash Wednesday, when many in the believing community submit to ash smeared foreheads and penitential posture, for all the world to see.

For-all-the-world—or a good bit of the Western world, even some in the believing community—interpret the day as an act of self-imposed suffering. Which is why a good many view the day, and the season of Lent, with much  skepticism, if not disgust.

skepticism, if not disgust.

Why would modern, civilized people—having been freed from the bonds of poor self-image—submit again to the servitude of crippling dependency? Does it not end in glorifying the obscenely brutal act of Jesus’ lynching? Of a cancellation of human liberty and freedom from medieval autocracy and serfdom? Some even argue the cross was divine child abuse.

You want to revoke the Enlightenment with Lent?

That’s where for-all-the-world is blind to the drama of Ash Wednesday and Lent’s invitation to penitence.

The promise of absolution for the penitent is what makes starting over possible. Think of the ghostly voice on your GPS announcing “recalculating” when you make a wrong turn.

The act of penitence is powered by the acknowledgment of grace. While the past cannot be undone, it need not determine the future. The fact that we make mistakes does not make us a mistake. The ability to acknowledge our weakness is in fact what makes us strong.

This is the alchemy of forgiveness: in knowing it, we are able to practice it. And in practicing forgiveness, our knowing grows wider and deeper.

The invitation to imposed ashes is not an act of subservience but of liberation from our disordered desires, from the market’s insistence that we are what we consume, that we are each on our own—no promises, no covenants, no communal bonds; only desires, interests, and accumulations.

In the real world, we are told, might makes right; only the strong survive; you own what you can take and keep. We are told, relentlessly, as one bumper sticker puts it: Those who beat their swords into plowshare will plow for those who don’t.

But there is another story.

My most vivid Lenten season occurred 25 years ago. For three years the Baptist Peace Fellowship board of directors devoted part of every meeting to engage in conversation about sexual orientation. We operated on a consensus model of decision-making. At least three members of the board were willing to do welcoming but not affirming to the presence of lgbtq folk in our midst. We were stuck.

Finally, though, in our February 1995 meeting, a fully-affirming vote was cast. It surprised us all.

As it happened, I was scheduled to begin my first-ever sabbatical at the end of that meeting, which was in Ft. Worth, Texas. I drove from there to a ranch in northeast New Mexico to begin my leave. But when I arrived, the first thing I had to do was get on a conference call with the board’s executive committee to plan a response to the firestorm of reaction to our board’s statement. Baptist publications which had never before mentioned our name were now printing full-page editorials of condemnation.

Long story short, I knew in my heart that this controversy could very well prove to overwhelm of our little organization. A good number of our own members and contributors were upset with the board’s decision. I spent untold hours walking the high desert pastures and climbing the mesas, dodging cow patties and watching pronghorn antelopes in the distance.

I sensed that my dream job was coming to an end. And I kept repeating in my mind all the good work we had done—and were doing, and would be doing—and asking why this should be lost. I was convinced what the board  had decided was the right thing to do. But I also sensed that it would prove to be our undoing. There was no turning back now. It felt for all the world like an impending death.

had decided was the right thing to do. But I also sensed that it would prove to be our undoing. There was no turning back now. It felt for all the world like an impending death.

I can’t say where exactly, or when; but my hopes for hanging on finally “died,” so to speak. I finally got to the place of accepting what seemed to be inevitable: that I would have to administer the end of our work—work which I had a key role in creating—and find a new career, not to mention a different source of income.

It was only that relinquishment, that apparent end of my personal dream—which felt like death—that I fell into the arms of a restful peace, which is what we call hope.

Lent’s call to penitential living is not feeling bad about yourself for some mistake you’ve made. It’s not punishing yourself, which somehow makes God happy. Lent’s penitential invitation is to an orientation acknowledging that we come from God, that we live in God, and that we return to God.

Lent’s invitation is to recognize that nothing—not even our failures, not even the ending of our most noble dreams—not even death—can separate us from the love of God. It’s to recognize that nothing is wasted. It is to recognize that there is a buoyancy in the world that we do not create, that we do not manage, that we do not fund. There is, in the lyrics to that old hymn, a great faithfulness which we can count on, whereby “morning by morning new mercies I see.”

This is the freedom to which Lent invites us. Having been freed from the presumption that we have to make the world right, we are able to relinquish the need to use violence—physical or emotional—to maintain breath. As we are released from being consumed with our own safety and security and applause, that’s when we are freed to pay attention to the ash heaps, to mingle with those who cannot do us favors or help us get ahead or bolster our reputations.

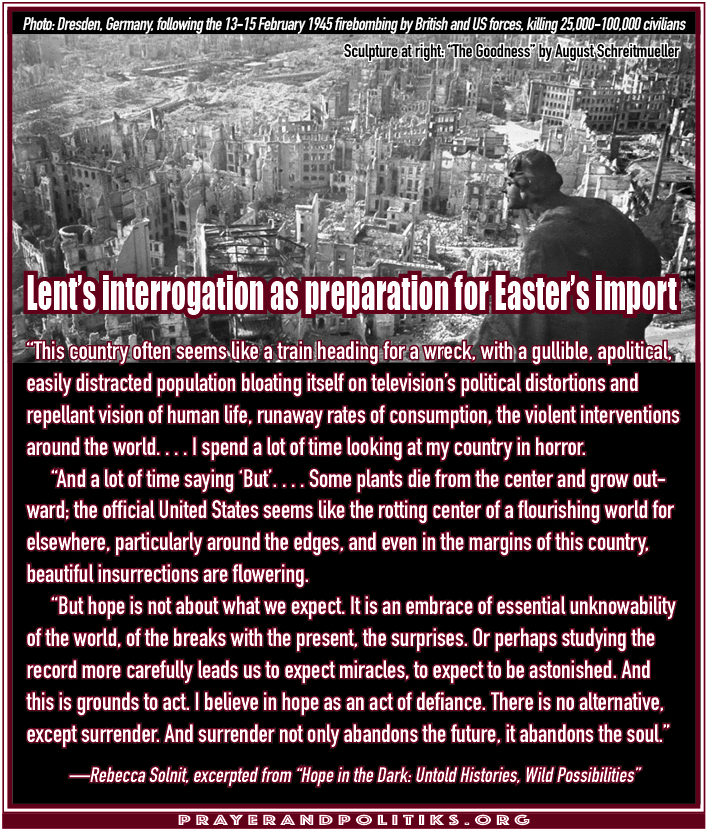

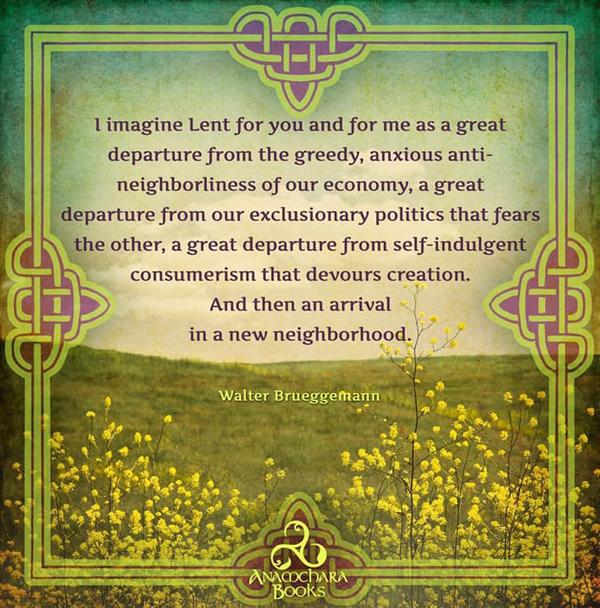

Lenten works takes us into the wilderness with Jesus, where resources are scarce. Lent demands that we take a hard look at the compromises we’ve made, the temptations to which we have succumbed, to secure our place in the world. Lent invites us to consider how our desires have become disordered and dangerous; our days cluttered and anxious; our relations strained and destructive.

I won’t take time to fully unpack the text from Matthew about the temptations Jesus’ faced while in the desert. Just remember this: every one of those offers the devil made to Jesus includes a veiled reference to a text in the Bible. The devil, too, can quote Scripture. Or, as William Sloan Coffin put it: “Like any book, the Bible is something of a mirror: if an ass peers in, you can’t expect an apostle to peer out!” Or as the Bible itself says, “There are some [texts] which the ignorant and wicked twist to their own destruction” (2 Peter 3:16b)

Jesus’ refusal to don the robe of royalty, the power to own and dictate and assume the presumption of power—this was the key to his freedom, the kind of freedom that enabled him—and enables us—to move toward the world’s ash heaps, to stand in resistance to the forces of shame and injustice.

It’s from the ash heap God is seen. Always, always from the ashes. Ash Wednesday, and the Lenten days that follow, is God’s program of theological education.

I love the way singer-songwriter Kris Kristofferson puts it: “Freedom’s just another word for nothing left to lose.”

This freedom work involves immersion in prayer—in honest transparency and correction and self-surrender to a purpose greater than our own skin. For us, that purpose looks like Jesus.

This self-surrender of prayer then propels us into self-surrendering, reconciling work in a world of hurt.

Several years ago I lived in South Dakota for eight months, taking care of my sister during her dying days, as well as Mom, who lived with her, Mom frequently looked at me and said, “I’m sorry you have to go to so much trouble, son.” And I would respond, “Mom, when you’re family, trouble is where you go.”

When you combine that with the way Jesus completely revised what “family” means—when you learn that family is more than tribe or clan, more than race or class or nation-state or any of the others ways we divide up who’s in and who’s out—you can see how Jesus’ vision threatened those who believed Almighty God had anointed them to ration grace, to enforce a quota on mercy, to demand a ransom for justice.

Stingy hands only know how to suppress trouble by coercive means. But Ash Wednesday’s smudge allows us to risk trouble, because trouble is where we go.

There’s a reason we celebrate Mardi Gras festivals and the sweet goodness of maple syrup on Shrove Tuesday, before we put on our Lenten crash helmets for the trials and tribulations to come. Trouble is where we go because underneath it all is a Great Faithfulness and the promise of new mercies to come. Keep this in mind in the troublesome days to come.

Sorry you have to go to such trouble, Circle of Mercy. But trouble is where we go.

# # #

sion that human value is calculated on usefulness and productivity. Having that fantasy stripped away is especially painful for those of us raised in a ethical universe shaped by capitalism. The makers find it impossible to believe we don’t get extra cookies; and that we don’t get to disparage the takers. What kind of moral mismanagement is this!?!

sion that human value is calculated on usefulness and productivity. Having that fantasy stripped away is especially painful for those of us raised in a ethical universe shaped by capitalism. The makers find it impossible to believe we don’t get extra cookies; and that we don’t get to disparage the takers. What kind of moral mismanagement is this!?! in the night of sorrow, remember the promise of joy’s release, for more is at work than we imagine.

in the night of sorrow, remember the promise of joy’s release, for more is at work than we imagine. coordination. “Apocalypse” is a tricky word. It evokes memory of the surreal 1979 film (“Apocalypse Now”) by Francis Ford Coppola and the mind-bending roles of Brando and Sheen and Duvall. Not to mention the glut of more recent dystopian movies and television shows featuring zombies and the trail of gore they dramatize.

coordination. “Apocalypse” is a tricky word. It evokes memory of the surreal 1979 film (“Apocalypse Now”) by Francis Ford Coppola and the mind-bending roles of Brando and Sheen and Duvall. Not to mention the glut of more recent dystopian movies and television shows featuring zombies and the trail of gore they dramatize. stars of heaven and threw them to the earth. Then the dragon stood before the woman to devour her child as soon as it was born.

stars of heaven and threw them to the earth. Then the dragon stood before the woman to devour her child as soon as it was born. ¶ St. Patrick Day festivities are many and varied. Even in my distance from all things Irish while growing up in a small tex-mex town in West Texas, and a slightly larger town down the Cajun swamps of South Louisiana, wearing green was a thing on 17 March.

¶ St. Patrick Day festivities are many and varied. Even in my distance from all things Irish while growing up in a small tex-mex town in West Texas, and a slightly larger town down the Cajun swamps of South Louisiana, wearing green was a thing on 17 March. pedal harmonium, Gerry O'Beirne, Mathew Manning, Moya O'Grady and David O'Doherty at Powerscourt House, 2009. Shaun Davey adapted the words of St Patricks Breastplate as translated by Kuno Meyer in 1990.

pedal harmonium, Gerry O'Beirne, Mathew Manning, Moya O'Grady and David O'Doherty at Powerscourt House, 2009. Shaun Davey adapted the words of St Patricks Breastplate as translated by Kuno Meyer in 1990. another million, reducing the country’s population by nearly 25%.

another million, reducing the country’s population by nearly 25%. nediction.

nediction. the music had a calming effect, just as I had hoped.

the music had a calming effect, just as I had hoped. skepticism, if not disgust.

skepticism, if not disgust. had decided was the right thing to do. But I also sensed that it would prove to be our undoing. There was no turning back now. It felt for all the world like an impending death.

had decided was the right thing to do. But I also sensed that it would prove to be our undoing. There was no turning back now. It felt for all the world like an impending death.

considerations. To be earnestly realistic about such choices, bridle your expectations, and orchestrate more forceful insistence for public character and righteous governance. As Bro. Douglass warned, power concedes nothing without demand.

considerations. To be earnestly realistic about such choices, bridle your expectations, and orchestrate more forceful insistence for public character and righteous governance. As Bro. Douglass warned, power concedes nothing without demand. nearby streets.

nearby streets. and hold fast to the One who made you.

and hold fast to the One who made you. an international movement now active in 56 countries. Local organizers specifically chose Valentine’s Day “to express love and support for NCEI scientists who . . . tell the truth about climate change.”

an international movement now active in 56 countries. Local organizers specifically chose Valentine’s Day “to express love and support for NCEI scientists who . . . tell the truth about climate change.” Their hearts are steady, they will not be afraid" (112:5-9).

Their hearts are steady, they will not be afraid" (112:5-9).