by Ken Sehested

Presentation for the colloquia on the theology of nonviolence,

Eastern Mennonite University/Seminary, October 24, 2002

Enough of this! —Jesus, Luke 22:38[1]

Opening meditation

It’s happening again. I guess I shouldn’t be surprised, and I’m not. But I always dread it: the conversations which, after some comment of mine, provoke in the listener those knitted brows and other facial expressions which convey incredulity, or at least a mixture of puzzlement and shock. And then, in vocal response, air from the lungs filters through the vocal chords, crosses the tongue and is finessed into speech by the lips. The infamous “p” word is spoken.

I always hate it when that happens. When it does, I always wonder if, secretly and unconsciously—despite my best intentions—I may in fact be the scoundrel (or coward or unrealistic dreamer) which the “p” word implies.

Sometimes when the “p” word is issued, the speaker is merely condescending rather than irate, as if to say: “Oh, you poor misguided soul. What a pity. Someone of your intelligence and commitment could actually be useful. What a shame; such a waste!” Which indicates I’m not so much a threat to the natural order of things as I am a freak of nature, a curious spectacle, occasionally entertaining and good for random humor, as if one of God’s jokes in an otherwise sober universe.

When the “p” word is spoken, I don’t know which I dread more: the speaker’s antipathy and anger or their belittling scoff.

Such a provocative word, the “p” word; capable of unleashing an avalanche of emotive response. A four-syllable word more distasteful than most four-letter obscenities.

You know the word. Concentrate for a moment. Among the majority of our citizens, even within the majority of Christian communities—particularly when spoken in a season such as ours when the drumbeat to war and the call to arms is infectious—what word beginning with the letter “p” is capable of invoking the emotions of fury and fright, or at least sneers and scorn, in otherwise sedate and rational people?

The word “pacifism,” of course.

Less than a century ago, during the first world war (the one billed as the final such conflict), conscientious objectors were actually hung by their thumbs just high enough so that the tips of their toes barely touched the floors of their cells. Of course, public etiquette has sufficiently changed so that pacifists no longer endure outright physical torture. That practice ended shortly before public lynchings of black folk.

There’s something to be said for cultural habits of civility which have developed among many industrialized countries. Freedom from being tortured for pacifist conviction is a good thing. But does this mean the message is getting through—or are the mechanisms of resistance and marginalization simply becoming more sophisticated?[2]

Commentary: Why I don’t often use the language of pacifism

I don’t often use the language of pacifism, for a variety of reasons.

In the first place, the word pacifism was not part of the cultural-linguistic vocabulary of my rearing. My world was formed in a small-town, Southern Baptist, working-class context—and significantly geared to the schedule and rhythms of church life—that was heavily colored by pietist and revivalist traditions. Although idealized “manhood” (for churched and non-churched alike) was characterized by gentility, the corresponding ethic of fair-play always upheld at least a proportionate option of retaliatory violence to protect the innocent. I’m not sure I would have known what “pacifism” meant if the word was used.[3]

Then, in my early adulthood migration (physically, culturally and theologically) to New York City and a more liberal religious subculture, the dominant intellectual presence was that of Reinhold Niebuhr’s “Christian realism,” with exposure to various emerging liberation streams of theology, both of which are (or were) critical of pacifist impulses.[4]

Second: I don’t use the language of pacifism simply because the word sounds like the word “passivity,” a verbal coincidence which, however misinformed (and regardless of the etymological histories of the words), reinforces the general public’s linguistic association of the terms—an association which is significantly dependent on the King James translation of one of Jesus’ pivotal commands in the Sermon on the Mount, “resist not evil” (Matthew 5:38), along with the concomitant phrase, “passive resistance.”

A dozen years ago, shortly before the outbreak of Operation Desert Shield (followed by “Desert Storm”—the U.S.-led coalition’s war with Iraq after its invasion of Kuwait), I received a letter from a long-time friend and Baptist pastor who was responded to some of the material the Baptist Peace Fellowship of North America (BPFNA) sent out in opposition to the war. My friend wrote: “I’m almost persuaded by pacifist convictions. But there are some things I simply feel are worth fighting for.”

Note, first of all, that the BPFNA didn’t use the word pacifism in any of our literature. (I’m not sure we ever have, except in printing articles by others who use that language.) The logical leap my friend made was this: opposition, or reluctance, to fighting for justice equals pacifism.

The passive posture might be on convictional grounds, e.g., in perceived obedience to scriptural mandate (“resist not evil”). Or, more commonly, on the instinctive human discomfort in confronting conflict. Or, on outright cowardice.

Consider the following quotes, the first by the Fascist Italian dictator Benito Mussolini, the second by British philosopher John Stuart Mill:

“Fascism believes neither in the possibility nor in the utility of perpetual peace. It thus repudiates the doctrine of Pacifism—born of a renunciation of the struggle and an act of cowardice in the face of sacrifice.” [5]

“War is an ugly thing, but not the ugliest of things. The decayed and degraded state of moral and patriotic feeling which thinks that nothing is worth war is much worse. The person who has nothing for which he is willing to fight, nothing which is more important than his own personal safety, is a miserable creature and has no chance of being free unless made and kept so by the exertions of better men than himself.”[6]

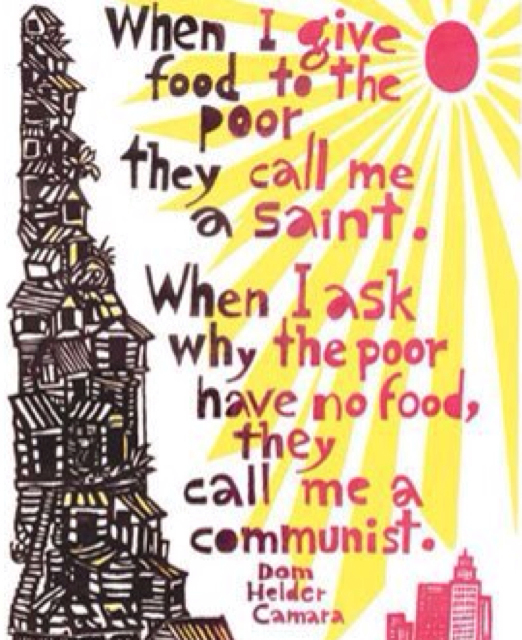

I quote these two disparate sources on purpose simply to underscore my point: that there is a widespread and deeply-rooted association in the public mind between pacifism and the avoidance of conflict (for whatever motive).[7] Correspondingly, I am convinced that maybe the most important thing Christians need to be emphasizing is the inevitability of conflict with established reality in lives committed to following Jesus.

To illustrate: “Pacifism” and “peace” are closely intertwined words in the English language. Note the meaning when someone says, “Leave me in peace!” or “Can I get a little peace and quiet here?” or when a protester is arrested on the charge of “disturbing the peace.”

Third: I don’t commonly use the language of pacifism because, in fact, the lived histories of pacifist communities are frequently predicated on the longing for personal moral purity than thirst for the Reign of God.[8] The dominant strain in such communities is an eschatological vision which, very much like my pietist/revivalist subculture, postpones the saving/redeeming/liberating work of Christ to metahistory, to “heaven,” to the world to come, a world in radical disjuncture with the creaturely world of flesh and blood. God’s work of Recreation is severed from God’s work of Creation. In such a theological posture, pacifism (usually accompanying other ethical mandates) becomes a substitute holiness code rather than a missional imperative.[9] Or, alternately, in those communities where rationalism controls theological conversation—where the emphasis is on doctrinal purity rather than personal holiness, nonresistance is added as an eighth plank to the seven traditional “fundamentals” of fundamentalism.

Of course, my friend Stanley Hauerwas has told me he’s willing to name himself a pacifist not because of reasons of holiness or doctrinal purity but as a means of being held accountable to a public commitment—for basically the same reason he’s willing to be identified as a Christian. And he has a point, logically; but, emotively, I’m not convinced.

Fourth: I shy away from “pacifism” language because of its typically single-minded focus on armed/military conflict. For instance, every pacifist organization I know about was founded as a response to the outbreak of war. To be a pacifist (like the more general term, “peacemaker,” only more pronounced) means to be against war.

Among the earliest and most painful lessons I learned when I began my organizing career some 25 years ago was that “peace” activists and advocates of social (economic) justice are significantly divided along racial lines. The “peace” community was (and is) largely concerned about the prospect of war—nuclear war, in particular—where social/economic justice advocacy groups tend to be composed of people of color.

A decade or so ago the BPFNA was considering contracting with a professional fundraiser to help with our development work. We found a good candidate—a seminary-trained, former Baptist pastor turned professional development expert—who we thought would be familiar with our constituency and with our theological/biblical vision. He agreed to donate a day of his time to meet with me and our board president to explore whether we might want to contract for his services.

At the beginning of our conversation he made a point of indicating his stringent ethical commitment against raising money for one purpose and then spending it on something else. That sounded good to us. So we began describing in some detail the various and sundry projects which the BPFNA had and was sponsoring.

In the middle of that recitation he interrupted to say, “You recall I said at the beginning how committed I am to ethical considerations. Well, I’m having a little trouble here. You call yourselves a peace organization, yet most of the projects you’ve described are related to justice issues.”

My board president and I were so dumbfounded by the question that we had a hard time responding. Here was a theologically trained person—surely he had been required to study the background of biblical words like shalom—who failed to make the connection between peace and justice!

Another anecdote from my organizing work: As you might imagine, nothing has brought more conflict to the work of the BPFNA than our 1995 board statement on sexual orientation. Although we felt it important to speak directly to this concern—and our conviction is opposite that of most religious bodies—we also knew it was important that we do more than issue a statement. In other words, we needed to actively promote and cultivate the occasion for dialogue and conversation. At one point we made a substantive proposal for such dialogue to the executive director of one of the several Baptist denominational bodies to which we relate. Shortly after that, in a chance hallway encounter at a Baptist convention meeting, the executive director—whom I’ve known personally for several years—thanked me for the proposal but then said, “I was a little confused though, since I thought you focused your work on peace issues.” Meaning, of course, war-and-peace issues.

One final anecdote: Shortly after the fall of the Berlin Wall in Germany, one of our most active members wrote us a jubilant note which began with the satirical question, “You folk got anything left to do?” As if the prospect of the end of the Cold War, including the nuclear threat, would mean we could close up shop and go home.

Fifth: I don’t often use the language of pacifism because of the typical context of debate regarding issues of political engagement: If not actively withdrawn from questions of public policy, pacifists usually are pictured as advocates of romantic, sentimental and utterly unrealistic options for shaping communal life. However well-meaning they may be, in the end they are actually stumbling-blocks to the just resolution of conflict. Their very innocence is in fact a refusal of public responsibility and creates dangerous blunder.

Recall, for instance, the classic movie “War of the Worlds.” Among the supporting characters is an elderly minister, father of the female lead whose role was driven by the inevitable romantic subtheme of such movies. The minister’s denominational affiliation is never indicated, but since he wears a clerical collar—and because he is openly identified as a parent—we’re left with the impression that he’s a high-church Presbyterian or Episcopal: very kindly, even grandfatherly. When public authorities initially mobilize against the intrusion (the space creatures have already executed the few humans initially encountered), all principle characters are huddled with military leaders in a defense bunker. A debate breaks out over the meaning of this invasion. Some—particularly the genteel pastor—argue that these creatures are probably friendly, would probably be amenable to dialogue, and should be trustfully approached. Others—particularly the civil and military leaders—argue against appeasement and for the assumption of hostility. As the consideration of options continues, camera angles focus on the clergyman’s deliberate and unnoticed withdrawal until, suddenly and with much alarm, the gathered defenders notice that the pastor has abandoned the protection of the bunker and is walking calmly, serenely, across the field toward the space invaders. And he is quoting the twenty-third Psalm with prayerful resolve masking his own trepidation. Just as he gets to the “Yea, though I walk through the valley of the shadow of death,” one of the alien crafts zaps him with its ray-gun appendage. This kindly, gentle, well-meaning but ultimately naïve, sentimental and foolishly reckless peacelover is burned to a crisp. Such is the realpolitik of the age. So much for pacifism.

Sixth: I don’t ordinarily use the language of pacifism because I am doubtful that a clearly definable, philosophically-precise line can drawn separating violence from nonviolence.

For instance, Gandhi’s advocacy of the spinning wheel—as a mechanism of undermining economic dependency on Great Britain—was a marvelously effective tool of nonviolent struggle. However, it was so successful a tactic that it led to widespread unemployment, exacerbating poverty and resulting in high levels of malnourishment in certain English industrial towns.[10] In the modern Civil Rights Movement the effective use of economic boycotts were experienced as a form of violence by white merchants—and functioned as such for working-class whites.

It is a truism to say that violence is hardly restricted to the antagonistic use of physical weapons. And, in fact, the book of James (3:1-12) employs some of the most scorching language in all the New Testament to warn about the destructive power of verbal violence. Thomas Merton, particularly, is well-known for his critique of the “violence” of protesters in the service of peacemaking.

Seventh, and finally: I usually refrain from the language of pacifism out of simple modesty. The truth is, few if any of us actually known how we would respond to violent attack short of a real-life encounter.[11] Espousal of pacifist conviction is inexpensive, and therefore unconvincing, when done from the comfort and safety of life in North America. Positions are relatively easy to stake and defend. Faithful communities should be more interested in taking action than in taking positions.

Whenever I’ve been asked, point-blank, if I am a pacifist, my response is: I’m willing to be tested.

So, what is the alternative to the language of pacifism?

[Following is an initial outline of the remaining part of this paper which I’ve not yet completed.]

–Considering the case made by Glen Stassen and others for “just peacemaking” as an alternative to the pacifism/just war debate.

–Reflection on the use of the paradigm of “transforming initiative” in organizing.

–Examining the possibility of a comprehensive, biblically-based narrative outline to support a comprehensive theological vision which begins and ends with nonviolence as characteristic of the nature of God; as fundamental in creation; as the driving orientation in the calling into being of Israel; as pivotal in the prophetic announcement (particularly Isaiah’s “suffering servant”); as central to the message of Jesus; and as the central organizing precept of Pauline theology (“the ministry of reconciliation”).

–Exploring the possibility of rooting this comprehensive vision in the biblical notion of sabbath? (Developing a “sabbatic theology”?)

# # #

[1] Rendering by Joel B. Green, The Gospel of Luke (Grand Rapids, Mich.: W.B. Eerdmans Pub., 1997), 774-775.

[2] I’m thinking here of the ritualized occasions of public demonstrations when civil disobedience is practiced, including highly stylized and pro forma arrests, much the way neo-colonial patterns of domination of one nation-state by another (and, increasingly, nation-states by transnational corporations) via economic rather than military penetration.

[3] A relevant anecdote: In the mid-1980s a staff person at the Southern Baptist Christian Life Commission (the social justice agency of the SBC, then still in control of “moderates”) called me for suggestions. Their newsletter usually featured a “point/counterpoint” article dealing with a particular social issue. The upcoming topic was pacifism, and my friend (who had a Ph.D. in ethics) was having a hard time finding a Southern Baptist pacifist to write for the issue. (I knew instinctively why I wasn’t being asked to write, being neither sufficiently well-known nor adequately in the mainstream.) My friend had already considered the suggested names I offered—they had already declined or were ruled out for other, more political reasons.) In the end, John Howard Yoder was enlisted to make the case for pacifism, one of the few times that (or most any other Southern Baptist) journal used authors outside the tribe.

[4] My seminary degree is from Union Theological in New York City, and I worked for Christianity & Crisis magazine—the journal founded by Niebuhr—the five years I was there.

[5] Benito Mussolini, quoted in P.M.H. Bell, The Origins of the Second World War In Europe, Second Edition, Longman: London and New York, p. 64;

[6] Quoted in a William L. May letter to the editor. The Denver Post, Sunday, Oct. 6, 2002, p. 2E.

[7] It would be fascinating to see the results of some empirical survey of the word “pacifism” as used in secular and religious sources. For instance, a search for the word and its cognates in several major daily papers; and, similarly, in several selected popular religious journals (other than those sponsored by the historic peace churches). Anybody know of such a study?

[8] I’m still unable to document the quote from distant memory: “Pacifists are a leech on the sins of others.” I’m pretty certain it doesn’t come from Reinhold Neibuhr, since neither Roger Shinn (a close friend and colleague of Niebuhr at Union Seminary) and Wayne Cowan (long-time editor of Christianity & Crisis) think this quote comes from Niebuhr. Maybe Paul Ramsey?

[9] Obviously, I need more documentation here that I can currently supply. Any suggestions for texts devoted to this subject (whether supportive of or contradictory to my assertion)?

[10] This reference is from memory of past reading and needs documentation.

[11] Combat diaries and histories are replete with stories of apparent leaders collapsing with fear when under fire; and amazing acts of bravery from those previously considered meekly unfit for leadership.

©ken sehested @ prayerandpolitiks.org

•join the protest (at this point it looks like the organizers are still welcoming allies on the ground, particularly those willing to help with the massive logistical challenges like food preparation and cleaning of all sorts)

•join the protest (at this point it looks like the organizers are still welcoming allies on the ground, particularly those willing to help with the massive logistical challenges like food preparation and cleaning of all sorts)

other states and oil company private security personnel, all heavily armed and supported by surveillance airplanes and helicopters, armored vehicles, even “sound cannons” (“Long Range Acoustical Devices” emitting ear-splitting noise).

other states and oil company private security personnel, all heavily armed and supported by surveillance airplanes and helicopters, armored vehicles, even “sound cannons” (“Long Range Acoustical Devices” emitting ear-splitting noise). Police Chief Andy Taylor’s disarming demeanor. No doubt there are hot-heads in both encampments. We can only hope that this swelling reservoir of mutual contempt does not escalate with fatal consequences triggered by an isolated, careless outburst.

Police Chief Andy Taylor’s disarming demeanor. No doubt there are hot-heads in both encampments. We can only hope that this swelling reservoir of mutual contempt does not escalate with fatal consequences triggered by an isolated, careless outburst. nation’s founding impulses, Paul VanDevelder writes, “In the end, says the Western writer William Kittredge, reconciliation will be America’s only way out of that legacy of dishonor, the only sensible path to a future worth living — our Last Chance Saloon.”

nation’s founding impulses, Paul VanDevelder writes, “In the end, says the Western writer William Kittredge, reconciliation will be America’s only way out of that legacy of dishonor, the only sensible path to a future worth living — our Last Chance Saloon.”

quit his job and travel the world.” But he managed to assure his Mom “I’m fine” with a series of dramatic photos. —

quit his job and travel the world.” But he managed to assure his Mom “I’m fine” with a series of dramatic photos. — life as a gift and who realize that the only way to honor such a gift is to give it away.” —William Stringfellow

life as a gift and who realize that the only way to honor such a gift is to give it away.” —William Stringfellow Cambridge University came to this conclusion by comparing the size of dozens of monkeys’ testes with the hyoid bones located in their voice boxes, which revealed a negative correlation between decibel levels and testicular endowment.” —

Cambridge University came to this conclusion by comparing the size of dozens of monkeys’ testes with the hyoid bones located in their voice boxes, which revealed a negative correlation between decibel levels and testicular endowment.” — McConnell, director of national intelligence under President George W. Bush. ‘It’s at least 75%, and going up,’ he says.” —Michael Riley, “

McConnell, director of national intelligence under President George W. Bush. ‘It’s at least 75%, and going up,’ he says.” —Michael Riley, “ As another political agitator, Jim Hightower, so aptly puts it in the title of one of his books, There’s nothing in the middle of the road but yellow stripes and dead armadillos.

As another political agitator, Jim Hightower, so aptly puts it in the title of one of his books, There’s nothing in the middle of the road but yellow stripes and dead armadillos. Hussain and Cora Currier

Hussain and Cora Currier Election Day. . . . A 51% majority of likely voters express at least some concern about the possibility of violence on Election Day.” —

Election Day. . . . A 51% majority of likely voters express at least some concern about the possibility of violence on Election Day.” — ¶ Just for fun. Four cellists, one instrument.

¶ Just for fun. Four cellists, one instrument.  baptist-affiliated congregations have dropped the word “baptist” from their name. This year’s Dahlberg Peace Award winners, Revs. Steve and Mary Hammond, can tell you about their congregation’s growth spurt after dropping “baptist” from their name. Unfortunately, in many places that public relations problem isn’t going away anytime soon.

baptist-affiliated congregations have dropped the word “baptist” from their name. This year’s Dahlberg Peace Award winners, Revs. Steve and Mary Hammond, can tell you about their congregation’s growth spurt after dropping “baptist” from their name. Unfortunately, in many places that public relations problem isn’t going away anytime soon.

agnostics / the Muslims and Jews / We need people of all nations / all colors and all creeds / to put an end to war, now / put an end to greed.” —Jon Fromer, "

agnostics / the Muslims and Jews / We need people of all nations / all colors and all creeds / to put an end to war, now / put an end to greed.” —Jon Fromer, " the door / And I've spilled wine on it all / Maybe I can paint over that / It'll prob'ly bleed through / Maybe I can paint over that / But I can't hide it from you.” —Guy Clark, “

the door / And I've spilled wine on it all / Maybe I can paint over that / It'll prob'ly bleed through / Maybe I can paint over that / But I can't hide it from you.” —Guy Clark, “ Regular Americans do this every day, in every community in America, and they need their leaders to do the same."

Regular Americans do this every day, in every community in America, and they need their leaders to do the same." possible that our puffed-up, prideful intelligence has outstripped our instinct for survival and the road back to safety has already been washed away. In which case there's nothing much to be done. If there is something to be done, then one thing is for sure: those who created the problem will not be the ones who come up with a solution." —quoted in Jake Johnson, “

possible that our puffed-up, prideful intelligence has outstripped our instinct for survival and the road back to safety has already been washed away. In which case there's nothing much to be done. If there is something to be done, then one thing is for sure: those who created the problem will not be the ones who come up with a solution." —quoted in Jake Johnson, “ Propaganda Joseph Goebbels said: ‘Churchmen dabbling in politics should take note that their only task is to prepare for the world hereafter.’” —William Barclay

Propaganda Joseph Goebbels said: ‘Churchmen dabbling in politics should take note that their only task is to prepare for the world hereafter.’” —William Barclay communities—a treacherous journey, since most of the roads were washed away—and is helping coordinate humanitarian relief.

communities—a treacherous journey, since most of the roads were washed away—and is helping coordinate humanitarian relief. ¶ For the beauty of the earth. North Dakota night sky (

¶ For the beauty of the earth. North Dakota night sky ( healing of the heart.” —Leonard Cohen, “

healing of the heart.” —Leonard Cohen, “ • “

• “ ned that an encounter with God—spiritual formation—has profound implications on both individual and corporate use of wealth.

ned that an encounter with God—spiritual formation—has profound implications on both individual and corporate use of wealth. “God” question is not a philosophical debate about the alleged existence of a Deity of some sort, of whether there is a Supreme Being that interferes in the “natural order.” The God question is a question about power. As Bob Dylan sang it so well, “you got to serve somebody.”

“God” question is not a philosophical debate about the alleged existence of a Deity of some sort, of whether there is a Supreme Being that interferes in the “natural order.” The God question is a question about power. As Bob Dylan sang it so well, “you got to serve somebody.” most prestigious measure of success. It’s making money. When you’re unable to make money you’re pushed to the margin.

most prestigious measure of success. It’s making money. When you’re unable to make money you’re pushed to the margin.